Laura Buckle

It

takes 9000 stitches to complete a full circle.

“The global textile industry is "one of the longest and most complicated industrial chains in the manufacturing industry" (Beton et al, 2014:13).

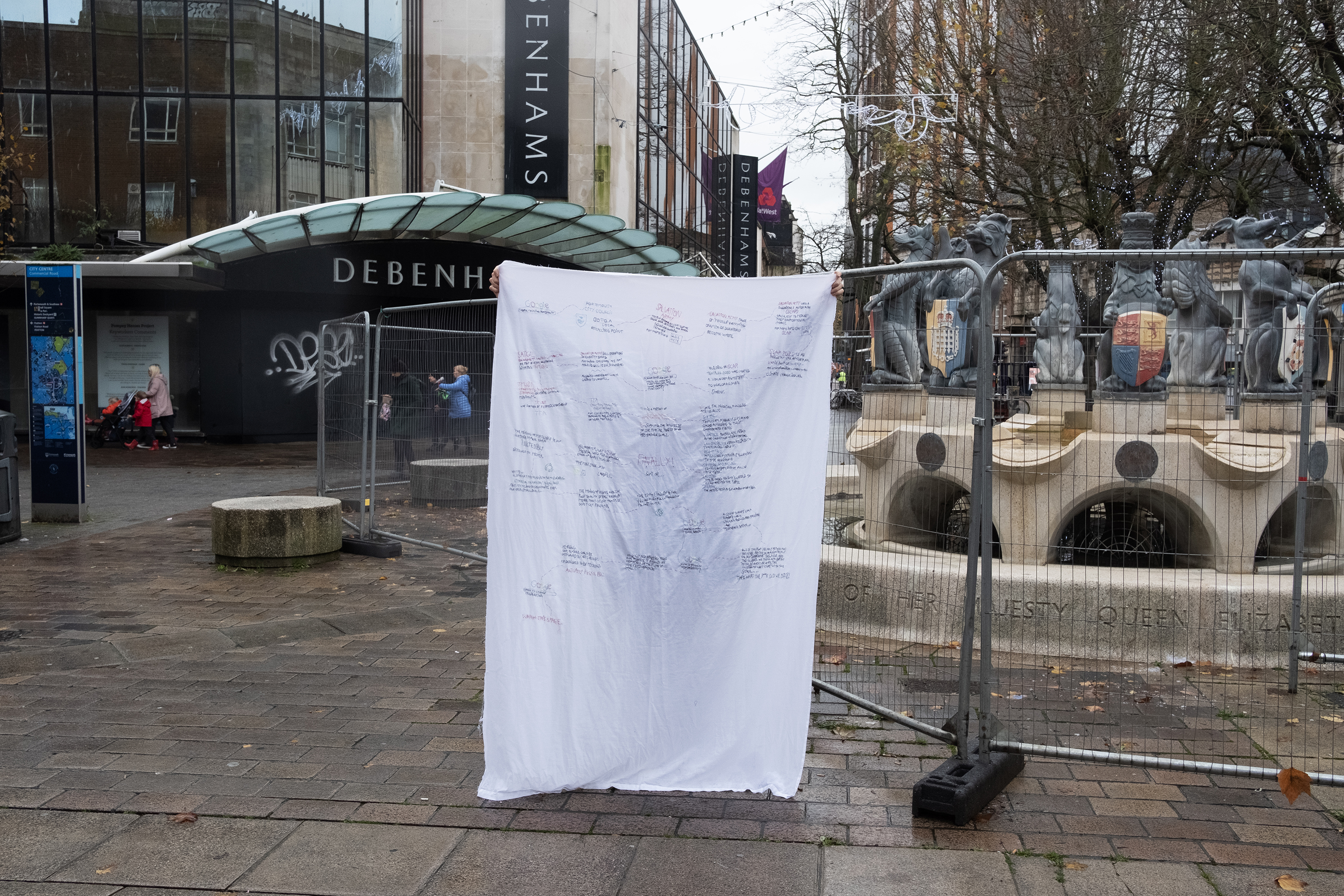

"It takes 9000 stitches to complete a full circle”, is a stop motion video composed of a little over 9000 images. Photographing a single hand stitch at a time, this video documents the journey I have undertaken researching the complicated and chaotic textile industry, and potential solutions. Situated in Portsmouth, a city on the south coast of England, 9000 stitches demonstrates how something as simple as a google search to find out what happens to our unwanted textiles is incredibly complicated, frustrating, and laughable. It shouldn’t be this difficult.

What clothes we wear directly impacts our planet, but we already know this. We already know that fast fashion is bad and unsustainable. We’ve seen the campaigns suggesting we buy second hand, or “recycle” our clothing. But here I propose a new campaign. One that might incite change and call out those responsible. One that highlights the issues of the current industry, without passing the blame onto those that have no choice, and one that will not stand for the continual depletion of land, and damage to human, and more than human life, all in the name of fashion.

Information around how to change legislation is equally as complex and impenetrable as the language used within the textile industry. There are however rumours and rumblings that changes to legislation is on its way, and soon textile producers will be responsible for their products' entire life cycle. Existing already in some countries, others, including the UK, are soon to be subject to similar legislation (extended producer responsibility (EPR)); apparently.

New legislation that enforces extended producer responsibility has the potential to drastically change the way our textiles are produced and better yet, how they are recycled. However, if EPR is enforced without a global and inclusive thought process, it’s unlikely to contribute to the efforts of those already combating the climate crisis. Globally there are some legislations that cover producer responsibility for products such as electrical goods. In France, the government want to reduce packaging and textile waste and their legislation states that “Anyone responsible for placing packaged products on the market must pay a “eco contribution fee” for the recycling of their packaging waste. Manufacturers in France must also take responsibility for textiles that are put in circulation” (Bettinl, 2021: n/p). However, when you buy an electrical household appliance in France," there is always a small part of the price labelled éco-participation, a fee used to fund collection and recycling of the item when it is no longer used. The money does not go to the government but to one of two non-profit organisations responsible for recycling” (Connexion France, 2019).

In other words, the cost is passed onto the consumer.

An inclusive circular economy, that is, one that does not exclude people from climate change solutions because of their race, class or gender, would not conclude with a solution where companies enforce a cost to the consumers.

One might argue that companies unable to absorb such costs, should reconsider making products that require such a pricey end, and perhaps redesign the way their textiles are made all together.

My point is that even when legally enforced to ensure products are recycled, companies will still find a way to dodge, mislead, pass the buck and greenwash all those involved in the textile industry, including the consumer. Although I am not dismissing the fact someone must pay to safely recycle or dispose of our products, and that consumers should not contribute, this is a privileged, upper/middle class standpoint that not all can participate in. If many of the working class are unable to contribute financially to the recycling of their products, the likelihood is, they will be unable to purchase the product to begin with. Already we see this pattern in fast fashion; author Abigail Allan discusses climate change and the UK's working class, and responds to the suggestion that consumers should consider the quality of their items before purchasing, as a means to combat pollution. Allan states;

"In the cycle of poverty, the working class consumer cannot afford to buy a high-quality, and therefore expensive, pair of boots, and so is forced to constantly and frequently buy and replace cheap pairs of boots. Furthermore, in my own experience, poorer members of society are more likely to not be able to afford a car and its associated costs, or even public transport, and so will walk more often, often over longer distances, meaning our cheap shoes are likely to wear out even more quickly. Buying more expensive, higher quality items is an investment that pays off both ecologically and economically - but people who don’t have the spare income to invest in higher quality items are stuck with an alternative that is worse for both their financial situation, forcing them further into the cycle of poverty, and for the planet. This forces the consumer to buy more products more often, forcing them further into the cycle of poverty – and inevitably increasing their climate impact" (Allan, 2020: n/p).

Without sociological context there is not a simple solution. Working class people may not have the option to avoid fast fashion, particularly with our current social crises. A non-consumerist approach to a circular economy may lead to class limitations and it would thereby suggest that the global industry need not create a complicated system, but scale back the current one; think necessity.

If production merely responded to need, as opposed to desire, the social, economical and environmental strain would be reduced enormously. In order for this sociological change, environmentalism must not exclude or target others. Author Jennifer Westerman reviews working class scholar and activist Karen Bell’s book; Working-Class Environmentalism: An Agenda for a Just and Fair Transition to Sustainability. In it,

“Bell calls on her readers and others to build a more inclusive environmentalism that will ‘benefit, include, and respect working-class people’ (p. 138). Learning from the environmentalism of the world’s poor efforts by trade unions to address environmental problems, and social movements for worker health and safety will enable a radical socio-ecological transformation. Bell asserts: ‘we must build alliances between social and environmental movements and extend these movements to support the widest scope of humans and ecologies possible'" (Westerman, 2021: 150).

As this issue is global, there is no quick fix or blanket solution that could possibly support everyone in the world. However it's with utmost importance that we stop the disempowerment and continuous beatings that the working class, Global South, and all others who are of a sociological and physical disadvantage, continually take.

If we are not careful, legislation change may replicate this pattern in different ways. We must ensure that there are no legislation loopholes that will allow companies to appear to be doing the right thing for the industry and our planet, but are in fact excluding many, whilst making no real change at all.

Legislation that ensures companies are responsible for a product's entire life cycle, must also ensure that what happens to the product is the same, regardless of who purchased it. Our current set up deliberately targets and blames those who are unable to participate any other way. There are of course exceptions to this; influencers and celebrities who don’t wear the same item twice, or the constant bombardment of social media and advertisers, desperately applying pressure for us to consume, consume, consume. I am not ignoring these facts, nor am I saying they are not incredibly problematic and detrimental to the way in which the industry is run. However I am saying that it is my belief that over time we can change these attitudes and behaviours for with them; comes choice.

I am standing for those that have no choice. The people in the Global South, the working class, the poor. I am standing for the workers in elastane factories becoming sick from the toxic chemicals, for the independent companies, scientists and researchers creating better ways to make and dispose of our products. For the protesters, artists and organisations shining light on this global unfairness and stating that enough is enough.

It is for these people and more, that I implore not just my government in the UK, but for governments around the world to stop this ludicrousness and make it simple. For that is the fix: simplicity.

Working class environmentalism provides the opportunity to consider everyone, of all backgrounds and abilities. Its impact on the textile industry would mean less items produced, better quality items, and transparency around recycling and a product's end of life.

It is my belief that legislation change is the next step needed, to begin to make the global textile industry a much fairer, simpler place for all. However, my argument is that if you're a producer of a product, and the law states you are responsible for its entire life cycle, you must also be responsible for the interactions your product has with people and the landscape along the way. Is it sourced in a way that isn't detrimental to the land? Are the workers producing it being paid fairly and cared for? Are consumers buying an honest product without greenwashing? Can that consumer afford the time to repair? Is there a clear way to recycle? Can it go back to the land at the end of its life?

It is my belief that the law should recognise these interactions as responsibility, and producers should be held accountable. Not with fines, but with action, reprimand, and consequence. Without change the poor get poorer, the sick get sicker, and an unsustainable industry will continue to grow at the detriment to our planet.

It is important we shop second hand or from sustainably conscious and fair companies. It’s important that we reuse and repair our textiles, that we wear them more and wash them less. It’s important to avoid certain materials and read past the greenwashing, and it is important to donate and recycle our clothes. But not every option is possible for all, or easy to do, nor will any or all of those options combined change anything quickly. We need producers to take responsibility, and create a much simpler industry.

Perhaps the global textile industry may seem ambiguous, but in my campaign I intend to call out those responsible. I will fight for a fair legislation change, to ensure producers are held accountable. I will fight for better production, honesty and transparency, new technologies, and simplicity, and I ask you to stand with me in this fight where together we state that enough is enough.

I am campaigning for global change and I am fighting against global injustice.

Watch this space.

Allan, A, (2020) No Choice: Climate Change and the UK’s Working Class, [online] Accessed: 26.08.22. Available at: www.anthroposphere.co.uk.

Beton, A, Dias, D, Farrant, L, Gibo, T, Le, Y. Spain,G, (2014) Environmental improvement potential of textiles (IMPRO textiles), European commission, Joint Research Centre scientific and policy reports.

Bettin, L, (2021) Textile EPR recycling laws [online] Accessed: 10.11.22. Available at: www.ecommercegermany.com.

Connexion France, (2019) What is French eco participation fee and how does it work? [online] Accessed: 10.11.22. Available at: www.connexionfrance.com.

Westerman, J, (2021) A Review: Bell, K. (2020). Working-Class Environmentalism: An Agenda for a Just and Fair Transition to Sustainability.Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 6 Issue 1.