Fatima Alaiwat

compos[t]ing rhythms with

bokashi

Over the past year, I have developed a bokashi practice - a

method of fermentation-composting - centred around the composting of orange

peels. This has involved being enveloped in various transmutations and

intoxicating citrusy events. My contributions to this process have included

ripping fresh peels into the bin layered with bokashi bran, burying fermented

peels in soil, and attuning my senses to the wafting scents of hot soil, fungal

aromas and decayed oranges. Performing the various tasks needed to sustain the

bokashi released worlds of ‘sensory events’ that ruptured and permeated my home

space - like the arrival of guests or seasons that would last for days or weeks

in various volumes - my awareness dipping in and out with their shifts and

intensities.

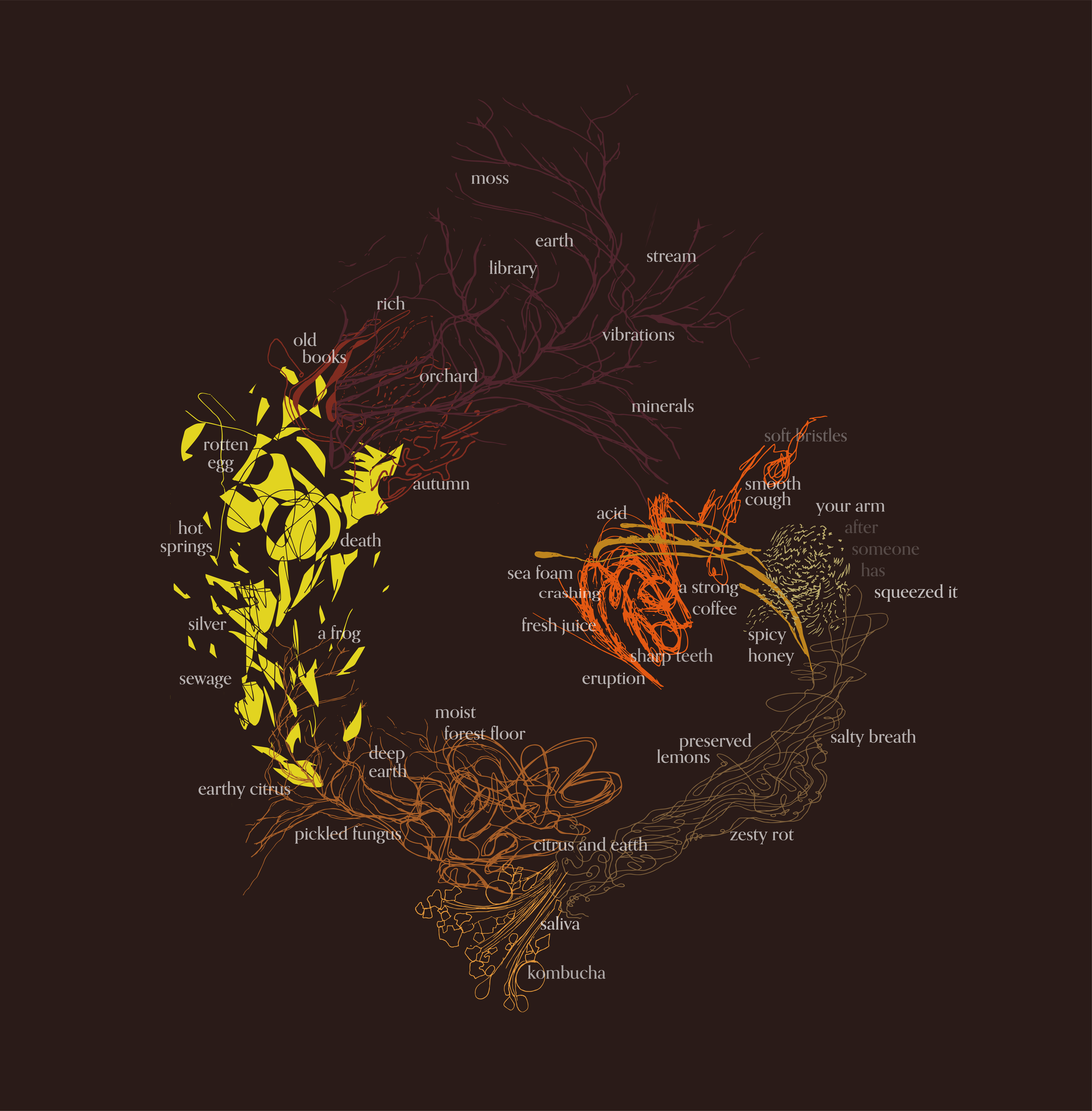

The image above represents a compilation of sensory events, constituting a host of entangled, overlapping, tangential and spiralling connections. With the awareness that ‘what soil is thought to be affects the ways in which it is cared for, and vice versa, modes of care have effects in what soils become’ (Bellacasa 2017, 170), I question how sensory intimacy with composting might serve as a way to lay down, cultivate and transform stories of belonging, whilst also practically improving the quality of soils that physically nourish our bodies.

The composting process is one that involves constant tinkering and amending: much like a recipe yet, in the case of bokashi, it is never complete. As a regenerative process, bokashi exists in constant cyclical rhythms. When the bokashi soil became too wet, I added cardboard and leaves. When there were too many pot worms, I added egg shells. The more we are required to tinker, the more we extend knowledge and experience, with potentially transformative effects on how we relate to waste, materiality and the spaces we inhabit. This continuous practice invites us to think about human engagement as a part of nature. There is no outcome, but a continuous process of seeking balance.

This embodies a key modality in my practice: a fascination for exploring dynamics of cyclical activations within the everyday, relating with our biological survival. This has continued to guide me towards the realms of the intimate, somatic, sensuous and body-centred ‘re/skilling’, as both practical and poetic modalities for exploring belonging and healing - or rather, ‘harm reduction’ (Kinnunen 2021) for alienated bodies, as well as quieter modes of resistance in the face of geopolitical issues and environmental crises.

Sandor Katz suggests that one of the most damaging aspects of our dominant food system is that it ‘deskills and disempowers peoples, distancing us from the natural world and making us completely dependent on systems of mass production and distribution’ (Katz 2020, 18). Optimistically, I question if cultivating more body-centred senses of belonging reskills us in earth-based epistemologies, that feel pertinent to building resilience in the face of environmental crises and fragile global food systems. Slowly, we ferment radical intimate relations with and in the homogenous and global.

Intimacy is an important and grounding aspect of my working process. I investigate how non-normative bonds with the more-than-human might facilitate accessible polycultures of knowledge, and provide alternative approaches to climate justice to that of the technocratic and scientific, despite dispossession. In his essay On Intimacy with Soils, Devon Peña talks about how his grandmother’s relationship with soil ‘encouraged are-membering of the body by means of affiliation with the land’ (Peña 2019, 277) and allowed her ‘to develop a deeper, more relational sense of place…[and] sense of partnership with the soil despite being far removed from any ancestral lands’ (Peña 2019, 277-278). When land is not owned and/or not home; how might we facilitate connection through caring for earth? I wish cultivating intimacy within small-scale, domestic composting as a way to foster a form of access and connection to land for alienated bodies, with the view that ‘the opposite of dispossession is not possession. It is not an accumulation. It is unforgetting. It is mattering’ (Morrill et al. 2016, 2). How can mattering be understood through bokashi as we reclaim soil relations through co-production in our home?

To be intimate with waste and microorganisms, as I propose with bokashi, opens a particular territory of reconfiguring relations with industrial food systems and the non-human, as a way to ‘craft new imaginaries for knowing, living and being with waste’ (Kinnunen 2021, 79). Caring for waste and, furthermore, sharing space in the home resists attitudes of ‘distance, disposability, and denial’ (Hawkins 2006, 16). How can this offer a way to shift understanding of belonging withand as part of nature, rather than within human social structures - particularly when social structures are ‘hostile to any attempt to put the individual back where he belonged’ (Fanon 1964, 53)?

How can a better representation and reverence for embodied knowledges serve to resist dominant capitalist, consumerist, colonial structures by seeking to attune with other forms of knowing, living, relating and learning? I question how ‘bring[ing] cognition down to earth’ (Mol 2021, 28) might better address complex issues that stem from such structures, by seeking to get closer to embodied and non-verbal forms of human intelligence. I do not propose this as a direct alternative to cognitive and intellectual modalities, but rather to think with how ‘the intellectual monoculture of science will be replaced with a polyculture of complementary knowledges’ (Kimmerer 2013, 139).

I wish to connect these words with the sensory events shared in the initial image compilation. Through personal experiences of living with bokashi in my home, I examine the intersection of probiotic, composting and embodied methodologies. Though the events were varied and extended to broadly embodied relationships, for the purpose of this writing, I focus primarily on scent and touch, as predominant features of living and relating with bokashi.

The image above represents a compilation of sensory events, constituting a host of entangled, overlapping, tangential and spiralling connections. With the awareness that ‘what soil is thought to be affects the ways in which it is cared for, and vice versa, modes of care have effects in what soils become’ (Bellacasa 2017, 170), I question how sensory intimacy with composting might serve as a way to lay down, cultivate and transform stories of belonging, whilst also practically improving the quality of soils that physically nourish our bodies.

The composting process is one that involves constant tinkering and amending: much like a recipe yet, in the case of bokashi, it is never complete. As a regenerative process, bokashi exists in constant cyclical rhythms. When the bokashi soil became too wet, I added cardboard and leaves. When there were too many pot worms, I added egg shells. The more we are required to tinker, the more we extend knowledge and experience, with potentially transformative effects on how we relate to waste, materiality and the spaces we inhabit. This continuous practice invites us to think about human engagement as a part of nature. There is no outcome, but a continuous process of seeking balance.

This embodies a key modality in my practice: a fascination for exploring dynamics of cyclical activations within the everyday, relating with our biological survival. This has continued to guide me towards the realms of the intimate, somatic, sensuous and body-centred ‘re/skilling’, as both practical and poetic modalities for exploring belonging and healing - or rather, ‘harm reduction’ (Kinnunen 2021) for alienated bodies, as well as quieter modes of resistance in the face of geopolitical issues and environmental crises.

Sandor Katz suggests that one of the most damaging aspects of our dominant food system is that it ‘deskills and disempowers peoples, distancing us from the natural world and making us completely dependent on systems of mass production and distribution’ (Katz 2020, 18). Optimistically, I question if cultivating more body-centred senses of belonging reskills us in earth-based epistemologies, that feel pertinent to building resilience in the face of environmental crises and fragile global food systems. Slowly, we ferment radical intimate relations with and in the homogenous and global.

Intimacy is an important and grounding aspect of my working process. I investigate how non-normative bonds with the more-than-human might facilitate accessible polycultures of knowledge, and provide alternative approaches to climate justice to that of the technocratic and scientific, despite dispossession. In his essay On Intimacy with Soils, Devon Peña talks about how his grandmother’s relationship with soil ‘encouraged are-membering of the body by means of affiliation with the land’ (Peña 2019, 277) and allowed her ‘to develop a deeper, more relational sense of place…[and] sense of partnership with the soil despite being far removed from any ancestral lands’ (Peña 2019, 277-278). When land is not owned and/or not home; how might we facilitate connection through caring for earth? I wish cultivating intimacy within small-scale, domestic composting as a way to foster a form of access and connection to land for alienated bodies, with the view that ‘the opposite of dispossession is not possession. It is not an accumulation. It is unforgetting. It is mattering’ (Morrill et al. 2016, 2). How can mattering be understood through bokashi as we reclaim soil relations through co-production in our home?

To be intimate with waste and microorganisms, as I propose with bokashi, opens a particular territory of reconfiguring relations with industrial food systems and the non-human, as a way to ‘craft new imaginaries for knowing, living and being with waste’ (Kinnunen 2021, 79). Caring for waste and, furthermore, sharing space in the home resists attitudes of ‘distance, disposability, and denial’ (Hawkins 2006, 16). How can this offer a way to shift understanding of belonging withand as part of nature, rather than within human social structures - particularly when social structures are ‘hostile to any attempt to put the individual back where he belonged’ (Fanon 1964, 53)?

How can a better representation and reverence for embodied knowledges serve to resist dominant capitalist, consumerist, colonial structures by seeking to attune with other forms of knowing, living, relating and learning? I question how ‘bring[ing] cognition down to earth’ (Mol 2021, 28) might better address complex issues that stem from such structures, by seeking to get closer to embodied and non-verbal forms of human intelligence. I do not propose this as a direct alternative to cognitive and intellectual modalities, but rather to think with how ‘the intellectual monoculture of science will be replaced with a polyculture of complementary knowledges’ (Kimmerer 2013, 139).

I wish to connect these words with the sensory events shared in the initial image compilation. Through personal experiences of living with bokashi in my home, I examine the intersection of probiotic, composting and embodied methodologies. Though the events were varied and extended to broadly embodied relationships, for the purpose of this writing, I focus primarily on scent and touch, as predominant features of living and relating with bokashi.

rip orange peels and

layer in the bin

sensing scents

fractured re/collections

Ripping orange peels to layer in the bin was a deeply energising sensory event. The oils erupted visibly as mist - softly drenching my body and surrounding elements in fresh zesty notes and gentle moist landings. The smell of citrus invoked for me very potent memories of an ‘elsewhere past’ (Chariandy 2007, 813), of particular people and places. I reflect on what it might mean to process particular foods and ingredient combinations when making bokashi, as one would with a recipe. As anyone who has had a cold can attest to, it is smell that mostly gives food its taste. To this end, a recipe or dish could be viewed as a curation of smell. How can this intense engagement with scent be translated to the context of curating waste smell with bokashi? Could living with a particular, augmenting smell, one that has a resonance with a practitioner’s cultural memory, serve as a way to cultivate belonging?

In The Politics of Taste and Smell: Palestinian Rites of Return, Ben-Ze'ev, Efrat discusses how ‘being able to make Msakhan everywhere you go has become a way of remaining Palestinian’ (Ben-Ze'ev 2004, 153). Though making certain foods has powerful associations with connecting people to cultures and home, I question how this applies in the context of waste. Unlike a fresh meal, which is ephemeral upon consumption, bokashi waste stays in the home. The waste is fermented and then buried, making the smells both ephemeral and lingering. I question how the smells of rot, decay and unprocessed ingredients of a particular recipe might capture the pain and potentiality of surviving and continuity in adversity. How might viewing bokashi practice as a mode of ‘cooking’ enable new ways of ‘recreating the features of a place to which one cannot return’ (Ben-Ze'ev, 153)? As fermented smells change, it is also a context that can push one to relating with smell in transit and transformation - a process in creating, changing and letting go. I’m interested in how such ephemeral and lingering practices can channel cultural memory.

To think further with notions of cultural memory, I engage with the idea of collecting waste over time, and how that might relate to recollection of memory. Initially, with my bokashi oranges, the familiar citrus scents invited fresh memories to coexist in my space: of Moroccan desserts, places, groves and street carts. As the fermentation process developed, these fresh familiar scents gradually began to take strange forms and I experienced them as ‘neither remnant, document, nor relic of the past, nor floating in a present cut off from the past’, but rather ‘links the past to the present and future’ (Bal 1999, vii). How might recreating smells within transformative practices create new assemblages that can help facilitate belonging as an alien body?

sprinkle bokashi bran

like dusting a table

to roll dough

ways of touching

muscle, memory

fluid barriers

all that is alive

I use my hands directly to feel the bokashi process when

layering the waste and bokashi bran, then press it well to ensure there is no

air. Afterwards I experience a tingling sensation in my hands. The bokashi bran

creates a reaction in my skin that causes my hands to tingle, what feels like

an echo of the touching process lasting long after I’ve stopped touching the

bokashi.

Touch is a powerful set of sensory experiences, with our fingers containing a significant amount of nerve endings that can sense a variety of different forms of touch: ‘some nerve endings recognise itch, others vibration, pain, pressure and texture. And one exists solely to recognise a gentle stroking touch’ (Cocozza 2018). How can developing more nuanced knowledges of touch, as well as touching more often, foster a body-centred sense of connection to place and belonging?

How does becoming physically entangled with a process through hands, rather than tools, offer a more connected experience and thus sense of belonging? In The Body Keeps the Score, Van Der Kolk discusses the notion of ‘sensory insensibility’ relating to a woman who suffered from PTSD, where she described how ‘it seems to me that I never actually reach the objects which I touch’ (Van der Kolk 2014, 82). Though this example makes a particular reference to trauma, I question how this can be understood in a wider sense. How might touch enable alienated bodies to ‘reach’ foreign land and distant homes? How might intimate touch with the non-human address sensory insensibility in the face of alienated experience?

Touch has been described as a form of species recognition (Cocozza 2018), that helps us to define distinctions and connections between self and other. I question how developing intimate touch with the more-than-human might facilitate an investigation of a less binary notion of self and of ‘other’. Furthermore, how might ‘species recognition’ extend beyond human relations? Studies have shown that touching soil, due to particular bacterias commonly found in soils, can increase serotonin production in the brain.1 How might this permeating exchange between human skin and soil be understood as an intimate relationship? How does intimacy relate with modes of care?

Touch is a powerful set of sensory experiences, with our fingers containing a significant amount of nerve endings that can sense a variety of different forms of touch: ‘some nerve endings recognise itch, others vibration, pain, pressure and texture. And one exists solely to recognise a gentle stroking touch’ (Cocozza 2018). How can developing more nuanced knowledges of touch, as well as touching more often, foster a body-centred sense of connection to place and belonging?

How does becoming physically entangled with a process through hands, rather than tools, offer a more connected experience and thus sense of belonging? In The Body Keeps the Score, Van Der Kolk discusses the notion of ‘sensory insensibility’ relating to a woman who suffered from PTSD, where she described how ‘it seems to me that I never actually reach the objects which I touch’ (Van der Kolk 2014, 82). Though this example makes a particular reference to trauma, I question how this can be understood in a wider sense. How might touch enable alienated bodies to ‘reach’ foreign land and distant homes? How might intimate touch with the non-human address sensory insensibility in the face of alienated experience?

Touch has been described as a form of species recognition (Cocozza 2018), that helps us to define distinctions and connections between self and other. I question how developing intimate touch with the more-than-human might facilitate an investigation of a less binary notion of self and of ‘other’. Furthermore, how might ‘species recognition’ extend beyond human relations? Studies have shown that touching soil, due to particular bacterias commonly found in soils, can increase serotonin production in the brain.1 How might this permeating exchange between human skin and soil be understood as an intimate relationship? How does intimacy relate with modes of care?

if the soil gets too

wet,

add leaves and

cardboard

shifting notes

bubble past walls

pulsing moments

timeless marks

At one point, I could see through the transparent container that the bokashi soil was particularly wet at the bottom. I emptied it all onto a large piece of cardboard to reveal an intense rotten-egg, metallic smell that occupied my home: sulphur. The smell permeated everything, including my fingers upon touching the soil. Scents are powerful in affecting our mental state and physical well-being, and the smell of sulphur is said to cause worry, anxiety and resentment.2 As a bokashi practitioner, ‘negative’ smells are ‘not something to turn away from, but they are rather considered as a form of communication: important messages that need to be taken seriously. Sometimes the bad smell is described humorously as a bucket’s ‘stinking objection to possible mistreatment’ (Kinnunen 2021, 73). This smell was telling me that the soil environment was too wet, which in turn prompted me to add cardboard and spread some particularly wet parts of soil out to dry.

This smell event also extended my engagement with materials beyond my home, as I needed to gather leaves. Walking to my nearest park, I felt a new sense of purpose and connection to this public space, as I collected leaves from the ground. I also leaned into the leaf-mould compost bin, where some leaves were still fresh and distinguishable, but others underneath were decaying - the fungal mouldy smells were intoxicating. I realised that as I dug my hand deeper, I was reaching through an archive of time: layers from spring, winter and autumn. My sulphur-infused fingers met with the earthy scents of leaf mould that were in varied states of transformation from previous seasons. Various scales of time and place were converging in deeply layered scents.

This experience of expanded networks encourages a planetary reflection on how we might foster care practises for the invisible and infravisible with the view that ‘ecological well-being depends on aligning the temporal dimensions of many beings, and the consequences of disruption and slippage between times’ (vi) (Bellacasa 2017, 176)? How does this relate with awareness and care for marginalised, ‘invisible’ communities and related colonial structures of violence? How might investing in relations beyond the ‘hegemony of vision’ (Elam et al. 2013, 139) teach us to inhabit the earth in a more peaceful coexistence?

curious collaborations

bodies, uprooted

shifting spaces

reaching for ground

After living with my bokashi bin for over 8 months, I had started to get very familiar and connected with the varied ‘shades’ of my orange bokashi smells. At the time of my Masters degree show, I moved all my bokashi elements to a small, empty white walled room where I was showing my work. With my bokashi materials in place, I was struck by how a sterile, ‘foreign’ space had become augmented with features of my home. Though only perceptible to me, this seemingly empty space now also contained features of home. Scents have the capacity to frame an experience and evoke powerful emotions, which has even been capitalised by ways of ‘scent marketing’ to manipulate customers into purchasing goods.3 In opposition to this, I consider how, by being particular to me, the orange bokashi scent-association with ‘home’ highlights a way of resisting large scale manipulative structures by fostering niche and particular scents that support creating safe spaces for minority communities. I question how, due to the fact that only particular people or groups might relate to certain scents, it can serve as a quiet form of resistance and resilience-building for marginalised peoples. How can we, through recreating smell, invite particular groups of people to belong and feel safe in public spaces?

I question this from a body-centred perspective - considering the materiality of cultural transmission and the gestures involved in the sensory ‘activations’ with bokashi practice. Thinking of cultural history as a sensory enactment, I am reminded of Anna Tsing’s description of someone sharing a recipe with her as ‘you have a fish. You add salt’ (Tsing 2015, 248). This highlights the tacit knowledge involved in cooking, where the trick is ‘in the bodily performance, which isn’t easy to explain…it is a dance that partners here with many dancing lives’ (Tsing 2015, 248). I’m interested in how this relates to accessibility, where other forms of knowledges are required to partake. How does this relate with safe spaces for marginalised communities and forms of kinship that are intentionally partially accessible?

Anita Mannur looks at this in the context of public eating spaces, in terms of rethinking ways to belong and not-belong to larger collectives by facilitating ‘intimate spaces of belonging (and unbelonging)...created for non normative subjects’ (Mannur 2022, 4). I question how these intimate spaces can be understood as body-centred experiences, exploring cultural memory as something that is ‘not merely something of which you happen to be a bearer but something that you actually perform, even if, in many instances, such acts are not consciously and wilfully contrived’ (Bal 1999, vii). What evidence does the body hold? What cultural traces are accessible to examine from the physicality of our existence?

In his novel Soucouyant, David Chariandy examines the complex unbelonging of second-generation individuals, writing ‘what … might his mother’s elsewhere past, uttered now in broken pieces, and in a language not entirely his, ultimately mean to him here and now, in apparently very different circumstances?’ (Chariandy 2007, 813). This captures elements of the complex fragmentation and ‘broken pieces’ of unbelonging for alienated peoples, and gestures towards how these might be incorporated into complex new identity narratives. How can regenerative composting practices, like bokashi, contain individual and collective histories and transform present contexts?

check on it,

but try not to disturb

hot pulses

warm blood

veins that touch

‘As Takalaiska gropes the pulp in the bucket with her bare hands, she engages in intimate contact with the living matter in the middle of its transformation process. Feeling the rising temperature is a means of knowing that although nothing has visibly changed, a great deal is happening.’ (Kinnunen 2021, 73)

One of the events of bokashi being buried in the soil is the strong heat that’s emitted around the waste area due to microbial breakdown of organic material. The heat could just be experienced as a binary sensation of ‘warm’ but, much like Takalaiska’s experience, it also has the potential to be experienced in a more nuanced and embodied way. The more I spent time touching hot bokashi soil, the more this heat and its associated knowledge of what is happening started to activate a deeper sense of experience of knowing and being. What was just ‘hot’ came to feel so much more. At first, the heat triggered an urge in me to dig into the bokashi soil and see what was happening in this heat. Over time, as my understanding of what was happening had grown into a knowledge of networks and of microbial worlds being built and digested, my reaction to the heat started to change. I no longer wanted to disturb it. In fact, I wanted to leave it as untouched as possible, and what once felt like a simple form of communication started to feel abundant in speaking to signs of activity.

As a bodily experience, I began to notice an experience of ‘soundscapes’ in my mind when I touched the heat - an abstracted world of motion and whispers. I have developed a rather intense imaginative world when I touch my warm bokashi soil, as human networks entangle with fungal and bacterial ones in the soil. This imagination is quite an embodied one: an auditory hum of a loud Moroccan family plays in my mind, and tangles with the physical sensation of the heat of the soil as well as my own warm pulsing blood. I offer this as a way to think of how home can be experienced as body-centred and performative. The experience of home has been described in phenomenology ‘as multi-sensory, where there is a blurring of clearly defined boundaries between the subject and object’ (Racz 2015, 15) and I question how multi-sensory and entangled intimacies with soil can support in ‘blurring of clearly defined boundaries’.

My touch and the sensation of heat created a communication between me and the soil, which in turn developed an intimate relation that transformed the way I touched the bokashi soil. I’m interested in how this connects with earth-based cultures in relation to climate awareness, and being able to respect and respond to invisible and infravisble entanglements. How might developing a physical relation with earth matter foster a sense of kinship and relatability with the more-than-human? How might that support migrants and displaced bodies in finding alternative modes of belonging, in the absence of stable human connections?

Repeat process

digestion upon digestion

never the same

time

I end this writing by sharing an intention to explore another cycle of inquiry stemming from notions around self-sufficiency and re-skilling. My research continues to guide me towards deeper sensuous realms within the everyday, in relation with the infravisible - spanning from the bacterial to the spiritual and communal. How might, in seeking autonomous modalities for biological survival, we respond to fragilities that arise from environmental crises whilst also creating new spaces for non-verbal modes of knowing? I question this in relation to bacterial inoculation and dynamicity of ‘contamination’ as practise. How might, for example, cultivating bacteria through foraging for Indigenous Microorganisms (IMOs) serve to reskill people and nourish soils whilst also connecting us deeply to land that may not be home? How can embodied self-sufficiency/interdependence with nature enable alternative ways of belonging and being with and on earth, despite dispossession?

I’m also interested in exploring the dynamics between action and inaction in relation to cultivation and conservation. This is something that I started to touch upon within my bokashi practice, where a deeper sensory engagement resulted in me increasingly leaving it alone. I question how non-intervention relates with our understanding of activism and productivity. How might we imagine productive in-activism or unproductive activism? How might non-productivity be cultivated? How could this speak to resistance to dominant capitalist structures? I wish to explore such tensions in conjunction with Buddhist philosophy as a means of addressing issues of ecological repair and alternative modes of belonging, being and knowing.

Footnotes

1. O'Brien ME, Anderson H, Kaukel E, O'Byrne K, Pawlicki M, Von Pawel J, Reck M 2004: SRL172 (killed Mycobacterium vaccae) in addition to standard chemotherapy improves quality of life without affecting survival, in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: phase III results. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15151947/ [Accessed 05/11/2022]

2. Fiedler, Nancy, Kipen, Howard, Ohman-Strickland, Pamela, Zhang, Junfeng, Weisel, Clifford, Laumbach, Robert, Kelly-McNeil, Kathie, Olejeme, Kelechi and Lioy, Paul 2007: Sensory and Cognitive Effects of Acute Exposure to Hydrogen Sulfide, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2199294/ [Accessed 05/11/2022]

3. Sanfilippo, Marisa 2022: The smells that make shoppers spend more, Available from: https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/3469-smells-shoppers-spend-more.html [Accessed 05/11/2022]

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke 1999: “Introduction” Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in the Present. Edited by Mieke Bal, Jonathan Crewe, and Leo Spitzer. Hanover: Dartmouth College

Bellacasa, María Puig De La 2017: Matters of care : speculative ethics in more than human worlds, Minneapolis, MN: University Of Minnesota Press

Ben-Ze'ev, Efrat 2004: “The Politics of Taste and Smell: Palestinian Rites of Return” The Politics of food. Edited by Lien, Marianne Elisabeth and Nerlich, Brigette:. New York City, NY: Berg

Chariandy, David 2007: Soucouyant, Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press

Cocozza, Paula 2018: No hugging: are we living through a crisis of touch? Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/mar/07/crisis-touch-hugging-mental-health-strokes-cuddles [Accessed 21/08/22]

Elam, Michele, Kina, Laura, Chang, Jeff, and Oh, Ellen 2013: “Beyond the Face: A Pedagogical Primer for Mixed-Race Art and Social Engagement” Asian American Literary Review, no. 2: 120-154

Fanon, Frantz 1963: The Wretched of the Earth, Farrington, C. (trans.), New York, USA: Grove Press

Hawkins, Gay 2006: The Ethics of Waste: How We Relate to Rubbish, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield

Katz, Sandor Ellix 2020: Fermentation as Metaphor, White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing

Kimmerer, Robin Wall 2013: Braiding sweetgrass : indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants, Canada: Milkweed Editions

Kinnunen, Veera 2021: “Knowing, living and being with bokashi”, Living with Microbes. Edited by Brives, Charlotte and Rest, Matthäus and Sariola, Salla. Available from: https://www.matteringpress.org/books/with-microbes [Accessed 31/08/2022]

Mannur, Anita 2022: Intimate Eating: Racialised Spaces and Radical Futures, Durham: Duke University Press

Mol, Annemarie, 2021: Eating in theory, Durham: Duke University Press

Morril, Angie, Tuck, Eve and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective 2016: Before Dispossession, or Surviving it: Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies

Vol. 12, No. 1. Available from: http://liminalities.net/12-1/dispossession.pdf [Accessed 1/8/2022]

Peña, Devon G. 2019: “On Intimacy with Soils: Indigenous Agroecology and Biodynamics” Indigenous food sovereignty in the United States: restoring cultural knowledge, protecting environments, and regaining health. Edited by Mihesuah, Devon A. and Hoover, Elizabeth, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press

Racz, Imogen 2015: Art and the Home: Comfort, Alienation and the Everyday, London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt 2015: The mushroom at the end of the world: on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Van der Kolk, Bessel A. 2014: The body keeps the score : brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma, USA: Viking Penguin