Introduction

Through the autumn of 2023, as the graduating cohort of the

MA Art & Ecology prepared their contributions to The Journal of Art

& Ecology, the necessity of linking ecology to questions of social

justice has seemed more urgent than ever. The work gathered here, by Aliansyah

Caniago, Sirun Chen, Rhiannon Hunter, Linnea Johnels, Jane Lawson, Sam Metz, Sohorab

Rabbey, Tina Ribarits, Elizabeth Salazar and Ella Wong, asks what it means to

be situated as an artist with a commitment to thinking and working ecologically

in the midst of planetary turbulence. At a time when settler-colonial violence, pollution and climate change denialism are surging, what artistic sensoria, tactics and

kinships might beckon towards more just and liveable forms of earthly life?

This 2023 edition of The Journal of Art & Ecology approaches dispossession and unfolding ecocide through sensorial memory, archival

investigation, material sensitivity and embodied knowledge. Much of the work makes

a critical challenge to the distancing techniques of extractivism and colonial

taxonomy, repurposing diagramming, mapping and digital capture to ask how we

might reconfigure our relations. The task of pluralising ecological knowledge

and attending to its historical omissions takes us into new methodological

territories – proposing autistic stimming as investigation, fungi as guides and

plants as healers of the cosmic body. Western epistemologies and capitalist

imperatives, which privilege certain kinds of bodies, are provincialized in

assemblages that combine the organic, the mineral and the technological, taking

their organisational logic from ancestral knowledge, acts of ecological care, Taoist

wisdom, neuroqueer phenomenology and decolonial feminism. In some contributions

the politics is outspoken, in others it appears as a haunting, in everyday

gestures of conviviality, or in quiet transgressions of translation. There are perspectives

that are tender and entangled, mournful and enraged, defiant and magical. It is

work that is not afraid to stumble through unfamiliar languages, to linger in

interstitial moments, to sit with discomfort and to recognise the radical

alterity of nonhuman creatures. It is art that is extending its antennae,

feeling its way towards deeper understandings of climate justice, mutuality and

recuperation.

Dr Ros Gray

Programme Director, MA Art & Ecology

Aliansyah Caniago

Rhiannon Hunter

assemblage - edit - collage - diffraction - story - cut - join - telling - anecdote - timespace - splice -

Reading [2 minutes 31 seconds]

Reading & Audio Visuals [4 minutes 28 seconds]

Reading & Audio Visuals [4 minutes 28 seconds]

1. Storying

To engage in land ecologies and conservation is to live with constant dilemmas around what and how decisions are made in the management of land, non-human and human beings, and what narratives are told and re-told.

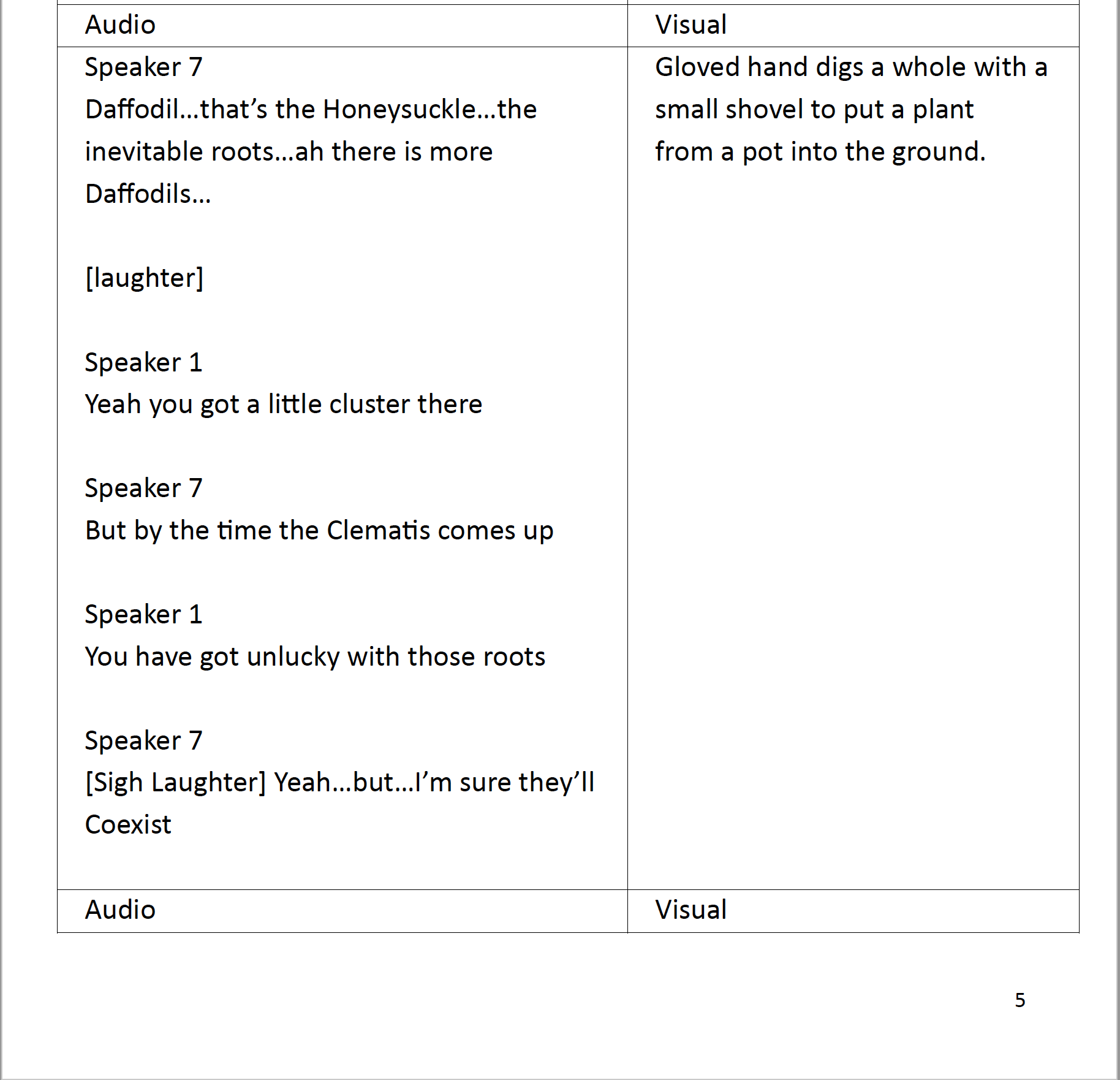

Doings of Care works across different modalities of information gathering, transfer and narration and seeks to echo the multiplicity of engaging with urban nature spaces. Amid fragmentary moments, meaningful questions surface about kinship, conservation, care and acts of noticing.

Doing involves participating in bodily actions of touch and attunement with other entities and beings that creates opportunities for knowledge transfer. To observe someone walking in water in waders is different to wearing waders and feeling the water’s power, its agency against one’s own body.

Silt, pebbles, grind underneath my steadying foot, my hips twist as the cool power of the water embraces my outstretched calf to funnel with giddy ease between my waders. [1]

The process of filming and image capture both documents and severs action’s ties with a specific time-location, to reconstruct events in a film-time-space through storying. Recorded sound waves are thick with data about their production, of bodily exchanges between other beings, of seasonality and colliding temporalities. Audible bird calls, flying insects, snapping branches, digging, a droning aeroplane, a hissing boiling kettle are layered sonics that drift into each other and disrupt scale and linear sequential events.This disruption speaks of the indivisibility of time and space as it is formed through ‘co-generation’” [2](Vogelin, 2023, p.46). Sound’s storying speaks of the interconnectedness and liveliness of all beings vibrating as one sonic-soup.

The gist is the essence of something summarised for ease of recollection and translation. They are mobile, fragmented gifts of information that move linguistically from one mouth to the ear of another. In doing so, they are imbued with metadata – a time(stamp), location, author, lived experience - that link them to a moment – to a non-event-event taking place that is relational between social beings caught in exchange. Gists move as an autonomous common currency of sharing knowledge that can provide insights that enable one to orientate oneself within the complexity of experiencing environments. Gists can move as an anecdote that ‘as it circulates it shapes the ways in which particular incidents come to be understood' (Micheal, M, 2021, p25) [3] They are rebellious forms of sharing that create haphazard social bonds and unofficial networks of exchange that evade dominant structures of ordering information, people and living worlds for capital gain and commodification.

![]()

Doings of Care works across different modalities of information gathering, transfer and narration and seeks to echo the multiplicity of engaging with urban nature spaces. Amid fragmentary moments, meaningful questions surface about kinship, conservation, care and acts of noticing.

Doing involves participating in bodily actions of touch and attunement with other entities and beings that creates opportunities for knowledge transfer. To observe someone walking in water in waders is different to wearing waders and feeling the water’s power, its agency against one’s own body.

Silt, pebbles, grind underneath my steadying foot, my hips twist as the cool power of the water embraces my outstretched calf to funnel with giddy ease between my waders. [1]

The process of filming and image capture both documents and severs action’s ties with a specific time-location, to reconstruct events in a film-time-space through storying. Recorded sound waves are thick with data about their production, of bodily exchanges between other beings, of seasonality and colliding temporalities. Audible bird calls, flying insects, snapping branches, digging, a droning aeroplane, a hissing boiling kettle are layered sonics that drift into each other and disrupt scale and linear sequential events.This disruption speaks of the indivisibility of time and space as it is formed through ‘co-generation’” [2](Vogelin, 2023, p.46). Sound’s storying speaks of the interconnectedness and liveliness of all beings vibrating as one sonic-soup.

2. The ‘Gists of Things

The gist is the essence of something summarised for ease of recollection and translation. They are mobile, fragmented gifts of information that move linguistically from one mouth to the ear of another. In doing so, they are imbued with metadata – a time(stamp), location, author, lived experience - that link them to a moment – to a non-event-event taking place that is relational between social beings caught in exchange. Gists move as an autonomous common currency of sharing knowledge that can provide insights that enable one to orientate oneself within the complexity of experiencing environments. Gists can move as an anecdote that ‘as it circulates it shapes the ways in which particular incidents come to be understood' (Micheal, M, 2021, p25) [3] They are rebellious forms of sharing that create haphazard social bonds and unofficial networks of exchange that evade dominant structures of ordering information, people and living worlds for capital gain and commodification.

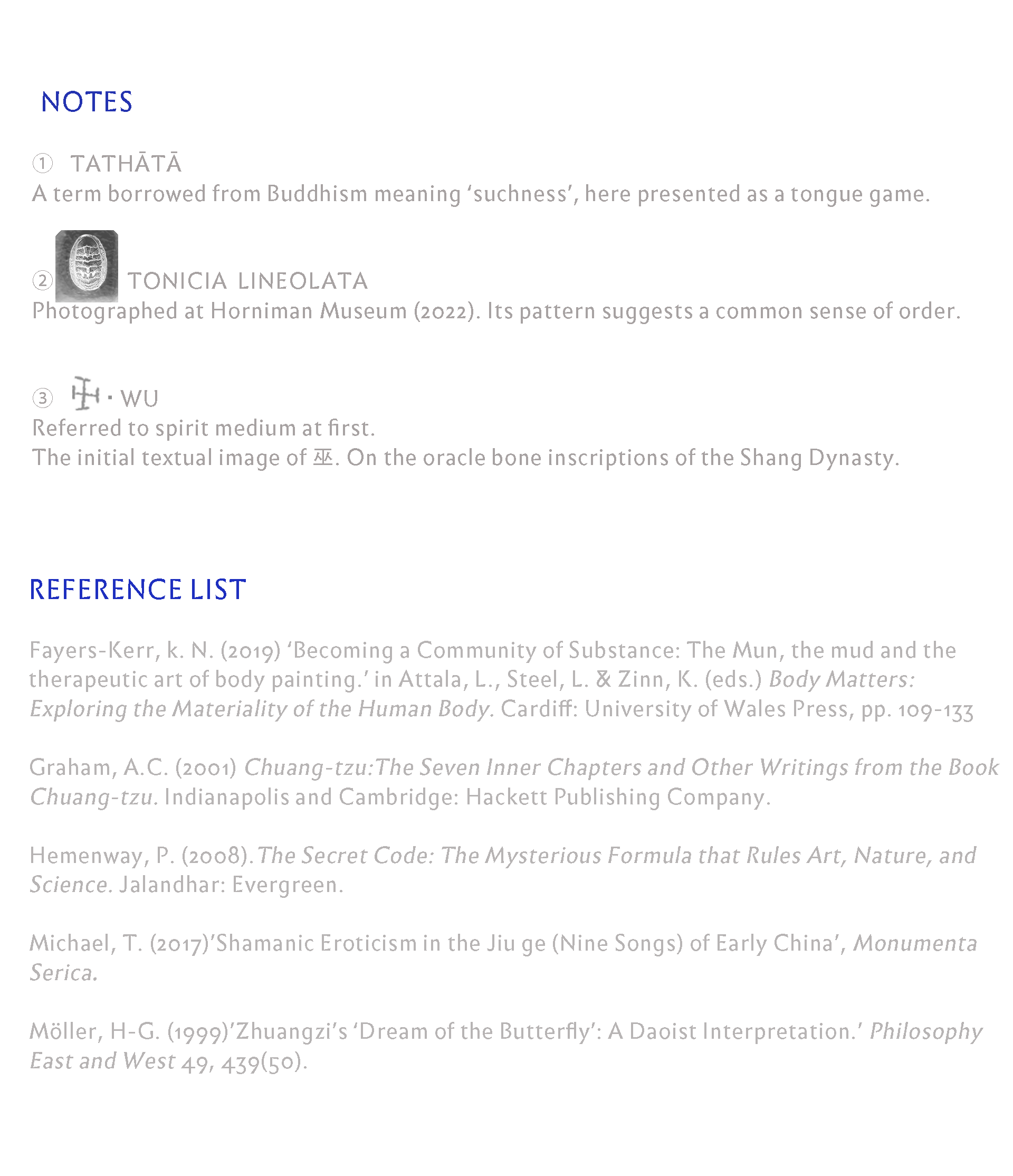

3. Care

Care is not

‘nice, cozy relations’ [4] (Abrahamsson and Bertoni, 2014, cited in Puig de la Bellacasa, 2015, p707). To

care is radical. It is a mode of engagement with self, other, human and

non-human that operates and generates its own value system aside from dominant systems

of accumulation and endless growth. Care is the time it takes for - and to film

- gloved hands that dig earth to make a hole for a plant to take root.

![]()

To undertake care is to dedicate time to the process of maintenance, reproduction and the ‘creating liveable and lively worlds’ [5] (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017, p.209) through everyday acts of doing, maintenance, noticing.

To undertake care is to dedicate time to the process of maintenance, reproduction and the ‘creating liveable and lively worlds’ [5] (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017, p.209) through everyday acts of doing, maintenance, noticing.

I

too enter the thigh-high water and attempt to coordinate my arms, torso and

cutters to remove the reeds. The air is sulphurous from disturbed pond matter,

breath and ice hover in condensing clouds, an upturned snail shell bobs, bitter

tea and bourbon biscuits, chattered talk, with engine hums. Volunteers trickle

away in different directions. My tyres have left a line in the ice

crisped grass as I stop recording, feet numb, I leave the common for the

tarmac. [1]

![]()

[2] Voegelin, Salomé (2023). Uncurating sound: knowledge with voice and hands. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

[3] Micheal, M. (2012), ‘Anecdote’ in Wakeford, N, and Lury, C (ed.), Inventive methods: the happening of the social,

[4]Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2015). ‘In Making time for soil: Technoscientific futurity and the pace of care’, Social Studies of Science, Vol. 45(5) pp. 691–716. DOI: 10.1177/0306312715599851 sss.sagepub.com

[5]Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). ‘Soil_Times_The_Pace_of_Ecological_Care’, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds, Minnesota Press, pp.169-215>

De La Bellacasa, M, P. (2017) ‘Soil Times: The Pace of Ecological Care.’ Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds, University of Minnesota Press, pp.169–216. JSTOR, Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1mmfspt.8. (Accessed: 19 Mar. 2023). Quote by Papadopoulos, Dimitris, 2011. “Alter-ontologies: Towards a Constituent Politics in Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science 41, no. 2: 177–201.

LaBelle, B. (2020), Sonic Agency Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance, London, Goldsmiths Press.

Todd, Z., Kanngiesser, A. (2020), ‘Attending to Environment as Kin Studies’

From digital forum Constellations. Indigenous Contemporary Art from the Americas, Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational and The Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Available: https://muac.unam.mx/constelaciones/assets/docs/essay-kanngieser-and-todd.pdf(Accessed: 2022)

4. References

[1] Journal Entries

[2] Voegelin, Salomé (2023). Uncurating sound: knowledge with voice and hands. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

[3] Micheal, M. (2012), ‘Anecdote’ in Wakeford, N, and Lury, C (ed.), Inventive methods: the happening of the social,

Routledge, p.25

[4]Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2015). ‘In Making time for soil: Technoscientific futurity and the pace of care’, Social Studies of Science, Vol. 45(5) pp. 691–716. DOI: 10.1177/0306312715599851 sss.sagepub.com

[5]Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). ‘Soil_Times_The_Pace_of_Ecological_Care’, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds, Minnesota Press, pp.169-215>

Also

De La Bellacasa, M, P. (2017) ‘Soil Times: The Pace of Ecological Care.’ Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds, University of Minnesota Press, pp.169–216. JSTOR, Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1mmfspt.8. (Accessed: 19 Mar. 2023). Quote by Papadopoulos, Dimitris, 2011. “Alter-ontologies: Towards a Constituent Politics in Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science 41, no. 2: 177–201.

LaBelle, B. (2020), Sonic Agency Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance, London, Goldsmiths Press.

Todd, Z., Kanngiesser, A. (2020), ‘Attending to Environment as Kin Studies’

From digital forum Constellations. Indigenous Contemporary Art from the Americas, Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational and The Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Available: https://muac.unam.mx/constelaciones/assets/docs/essay-kanngieser-and-todd.pdf(Accessed: 2022)

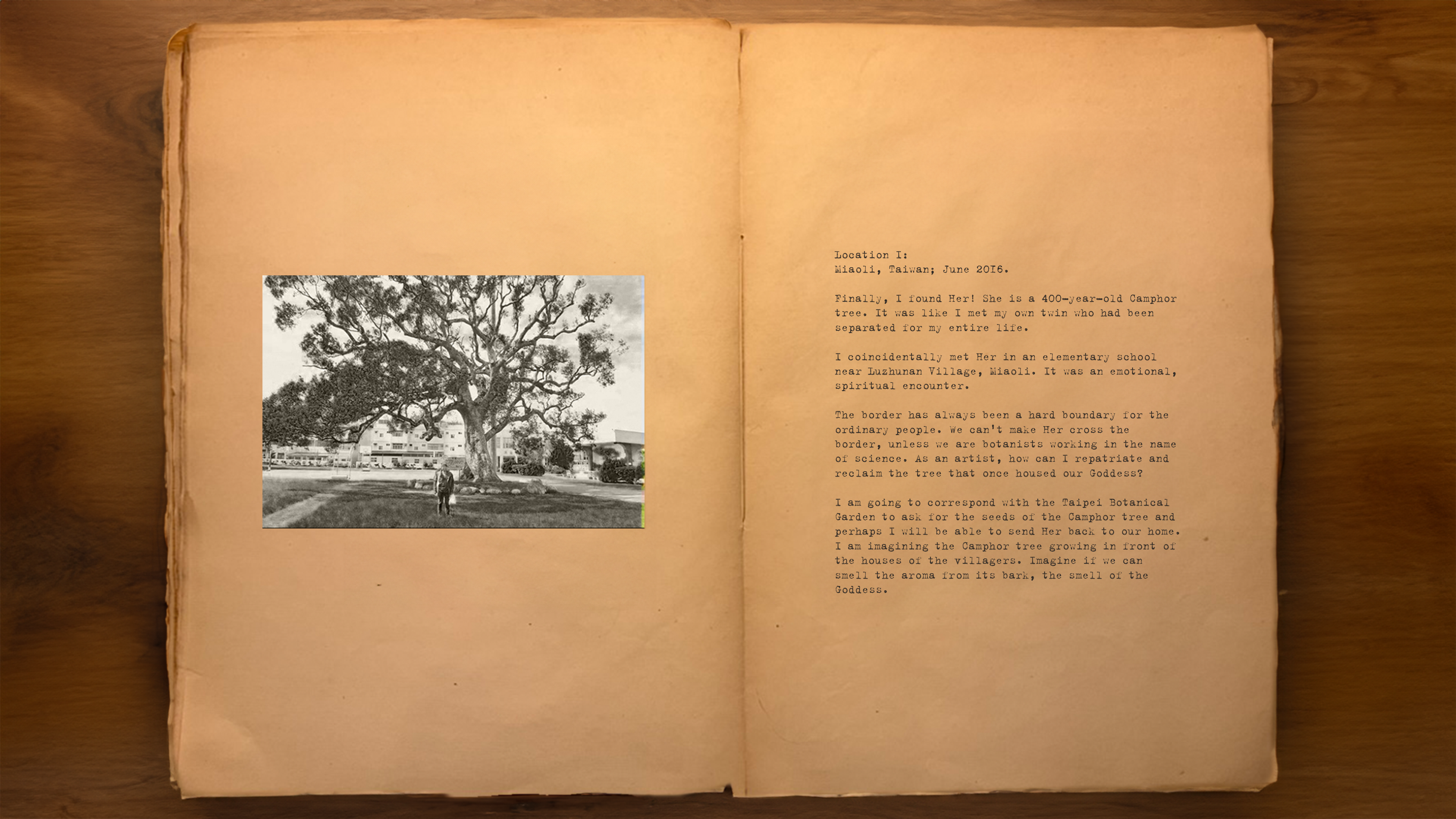

Linnea Johnels

An eponym is a taxonomic name based on a real or fictional person.

The Linnea flower Linnaea borealis was named after the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. He is known as the father of modern taxonomy. Linnaeus binomial nomenclature, a method of naming biological species with two consecutive Latin names, is now used worldwide.

On 10 January 2023, two zoologists met me at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. The year before, my father told me in passing that a fish had been named after my grandfather Alf. On that day in January, the two men from the museum showed me a specimen of the fish Chrysichthys johnelsi, collected by Alf in the Gambia. The pale orange creature was floating in a jar of alcohol, its mouth open and eyes shrivelled up, suspended in time.

Alf Johnels was born 27 October 1916 as

the youngest of six children to John and Elsa Andersson. John and Elsa decided

to merge their names to create the more original last name Johnels.

On 27 May 1950, my grandfather arrived in Bathurst, the capital of the British colony of the Gambia, together with two other scientists. They were on a research expedition with the aim to collect fish for anatomical and embryological research.

On 2 June 1739, together with five other men, Linnaeus founded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in Stockholm, modelled after similar societies around Europe. Their aim was to promote and teach relevant and useful knowledge to strengthen the society of Sweden with an emphasis on the economy.

On 27 May 1950, my grandfather arrived in Bathurst, the capital of the British colony of the Gambia, together with two other scientists. They were on a research expedition with the aim to collect fish for anatomical and embryological research.

On 2 June 1739, together with five other men, Linnaeus founded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in Stockholm, modelled after similar societies around Europe. Their aim was to promote and teach relevant and useful knowledge to strengthen the society of Sweden with an emphasis on the economy.

Like other Scientific Societies, the Royal Swedish Academy of Science collected curious and scientific objects for research and education. Many were collected in conjunction with European imperial expeditions. The Academy had a policy to keep its collection accessible to the public already in 1784 and it became an official state funded museum in 1819. The public was invited to exhibitions demonstrating how much of the world had been conquered by Europeans, demonstrating their asserted ‘superior’ structure of knowledge. The Academy was required to move several times during the years as the collection grew to include animals and items expropriated from all corners of the world. Finally in 1915, two palatial buildings were erected just north of Stockholm where the Royal Swedish Academy of Science and the Swedish Museum of Natural History are still located.

The Swedish Gambia Expedition of 1950 was a continuation of a previous Swedish expedition twenty years earlier. The country of investigation was inspired by a British zoologist who found species important for the research on the evolution of primitive fishes in the Gambia in the late nineteenth century. My grandfather’s expedition settled in Bansang on the south bank of the Gambia river, 300-km upstream from the Atlantic Ocean. They stayed in the vicinity of a hospital run by Europeans.

I walked through the corridors lined by cabinets and shelves stacked with preserved animals. The smell evoked memories from when I visited my grandfather at work as a child. Down in the basement’s security vaults, where the majority of the highly flammable collection is stored, the zoologists showed me specimens dating back to Linnaeus himself. Some species that have gone extinct, some specimens that were chopped up to anatomical pieces. In one of the bigger jars - a baby elephant.

The collection started

through donations from wealthy private collectors. Items continued

to arrive from merchants in the Swedish East India Company, from the Swedish colony of Saint

Barthélemy and from Linnaeus’ disciples. Anders Sparrmann, who famously

travelled with Captain Cook, donated a large collection of specimens after his

expedition to the Senegambia region in 1788.

The Senegambia region is the western point of the African continent, situated between the Sahel, the Futa Jallon plateau, and the Atlantic Ocean. It has a rich cultural history with empires like Ghana, Tekhur, Mali and Songhai, the kingdoms of Futo Toro and Gajaaga, the Kaabu and Jolof confederations. Because of its geographical position, Senegambia was the first region in Africa to come into contact with the Europeans via the Atlantic Ocean. First came the invading Portuguese traders, who dominated the area until the second half of the sixteenth century, then the French, Dutch and British entered in a competition for African resources. From the seventeenth century the slave trade dominated Senegambia. Devastating, large-scale manhunts were conducted, shattering millions of lives, leaving consequences that bleed into our present time.

The Senegambia region is the western point of the African continent, situated between the Sahel, the Futa Jallon plateau, and the Atlantic Ocean. It has a rich cultural history with empires like Ghana, Tekhur, Mali and Songhai, the kingdoms of Futo Toro and Gajaaga, the Kaabu and Jolof confederations. Because of its geographical position, Senegambia was the first region in Africa to come into contact with the Europeans via the Atlantic Ocean. First came the invading Portuguese traders, who dominated the area until the second half of the sixteenth century, then the French, Dutch and British entered in a competition for African resources. From the seventeenth century the slave trade dominated Senegambia. Devastating, large-scale manhunts were conducted, shattering millions of lives, leaving consequences that bleed into our present time.

The archive of the Swedish

Gambia Expedition is kept at the Swedish Museum of Natural History. Black and

white photographs and a travelog depict many of the local people helping the

Swedish researchers. Only one name was written down - Abdullaj.

The scientists examined the swamps and creeks, fishing with nets, lines and hooks, seines, traps, and with an electrofishing device. They bought some fish from the local fishermen. They walked through the muddy beds of the swamps or floated on the surface in a small boat. They monitored the water levels, rainfall, and temperatures, meticulously noting every change. They suspected the locals of stealing fish from their traps only to find out it was actually the crocodile.

The scientists examined the swamps and creeks, fishing with nets, lines and hooks, seines, traps, and with an electrofishing device. They bought some fish from the local fishermen. They walked through the muddy beds of the swamps or floated on the surface in a small boat. They monitored the water levels, rainfall, and temperatures, meticulously noting every change. They suspected the locals of stealing fish from their traps only to find out it was actually the crocodile.

In 1816 the British founded

the settlement Bathurst, and in 1820, they claimed the Gambia River as a

British Protectorate. They used the abolition of the slave trade as an excuse

to control the market and wanted

the river as an access point to gold deposits and other resources in the

interior of Africa. In 1889, after decades of rivalry over the area, they

reached an agreement with France and the Gambia-Senegal border was drawn

up. Cutting through already existing communities, the British

obtained the small strip of land shaped like the river it surrounds. The

Gambia stayed under British rule until the country

gained independence in 1965.

The collection of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science contained objects of all sorts, both cultural and natural. Some human remains had been collected based on the false belief of distinctly different human races and their inherent traits. The collection was divided in 1935, when an ethnographic museum was founded. In 1965, the independent Academy of Science had to let go of the state funded Swedish Museum of Natural History. Since then, both the Academy and the Museum have rebranded their relation to nature, changing how they articulate their role from collecting to protecting, becoming hard science institutions without a social context. They have created national parks and environmental protection around Sweden, shadowing its participation in the social history leading up to the need to protect it.

The collection of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science contained objects of all sorts, both cultural and natural. Some human remains had been collected based on the false belief of distinctly different human races and their inherent traits. The collection was divided in 1935, when an ethnographic museum was founded. In 1965, the independent Academy of Science had to let go of the state funded Swedish Museum of Natural History. Since then, both the Academy and the Museum have rebranded their relation to nature, changing how they articulate their role from collecting to protecting, becoming hard science institutions without a social context. They have created national parks and environmental protection around Sweden, shadowing its participation in the social history leading up to the need to protect it.

My grandfather had a

successful career as a scientist. He became a professor at the Swedish Museum

of Natural History, and later the director of the museum as well as the head of

research. He was accepted as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science

1972 where he held the presidency between 81 and 83. During his career he was a

pioneer in the research of environmental toxins such as DDT and mercury,

conducting research on taxidermy specimens from the natural history collection.

Alf visited the museum daily until late in his 80s. He died in 2010, at the age

of 93. On his coffin was the emblematic Linnea flower, a symbol for his

biological interest.

Attributing a name to a species after a person is more than just naming, it is a statement of that person’s achievements and station. It often gives importance to one knowledge system over another.

The Chrysichthys johnelsihas many names, each conjuring a world.

Fouthiole

Ba-sagoin bethguye

Kibbie

Korsie

Attributing a name to a species after a person is more than just naming, it is a statement of that person’s achievements and station. It often gives importance to one knowledge system over another.

The Chrysichthys johnelsihas many names, each conjuring a world.

Fouthiole

Ba-sagoin bethguye

Kibbie

Korsie

Notes

Footage from the Swedish Museum of Natural History 2023, shot with the same Keystone K-8 double 8 camera that Alf used in the Gambia 1950.

References:

Barry, Boubacar, and American Council of Learned Societies (1998) Senegambia and the Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York: Cambridge University Press

Frängsmyr, Tore (red.) (1989). Science in Sweden: the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1739-1989. Canton: Science History Publications

Johnels, A., G., (1954). Notes on fishes from the Gambia River. Ark. För Zool. Stockh. 6, 326–411.

Guedes, P., Alves-Martins, F., Arribas, J.M. et al. Eponyms have no place in 21st-century biological nomenclature. Nat Ecol Evol 7, 1157–1160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02022-y