Dance of dao among words

Ella Wong

‘The origin of philosophy is translation or the thesis of translatability.’

- Jacques Derrida (1985,120)

‘The origin of philosophy is translation or the thesis of translatability.’

- Jacques Derrida (1985,120)

Notes

on translation

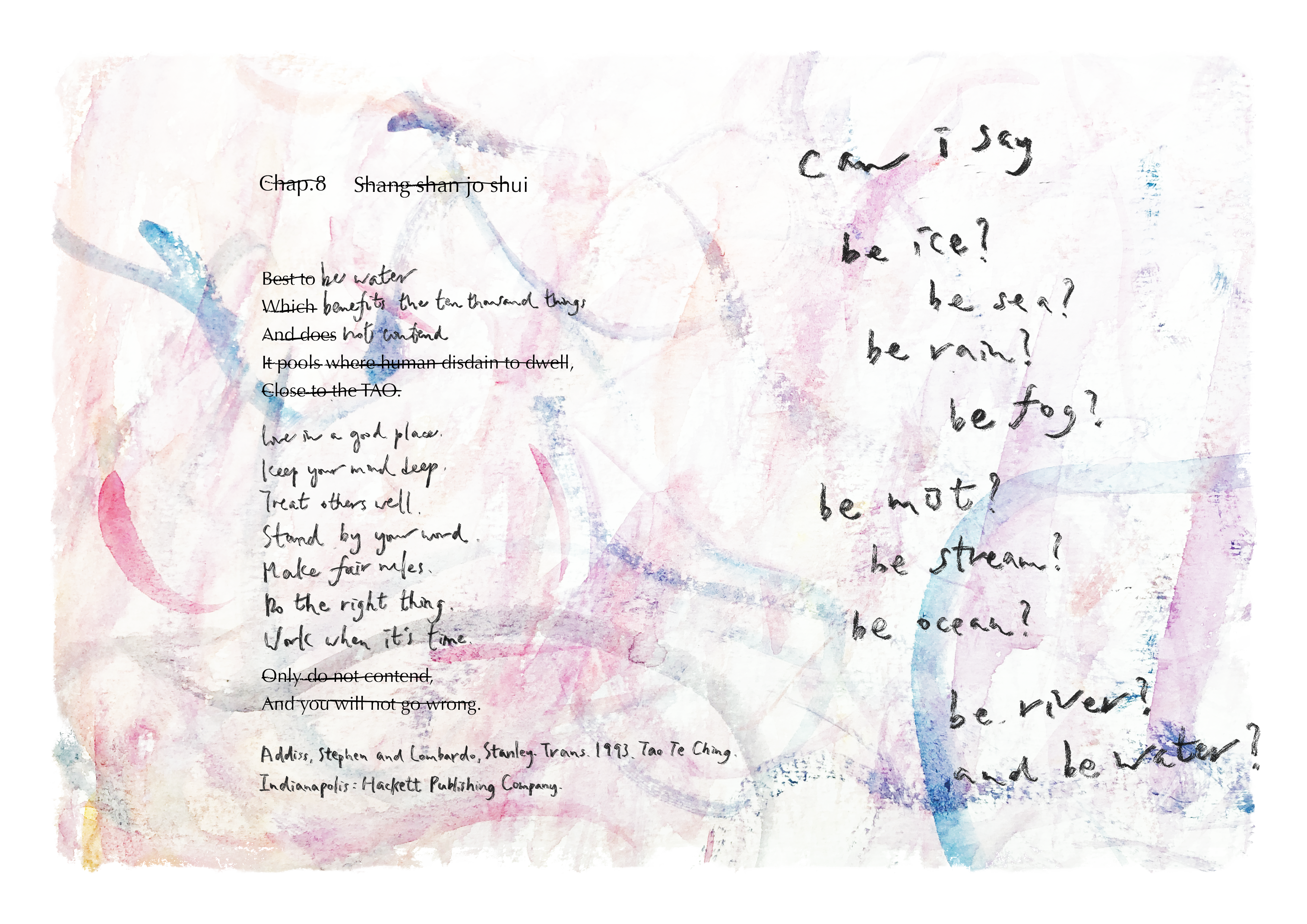

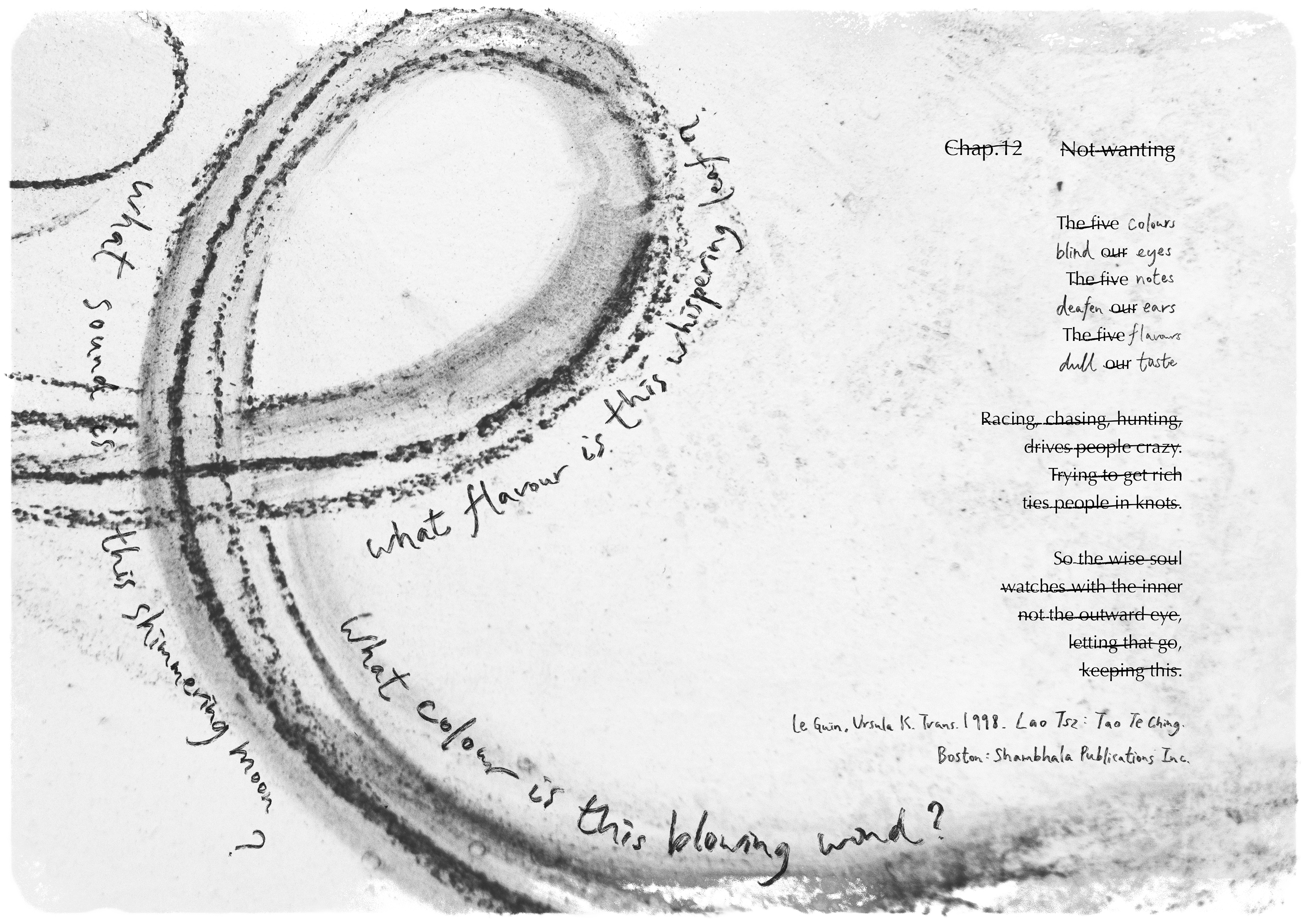

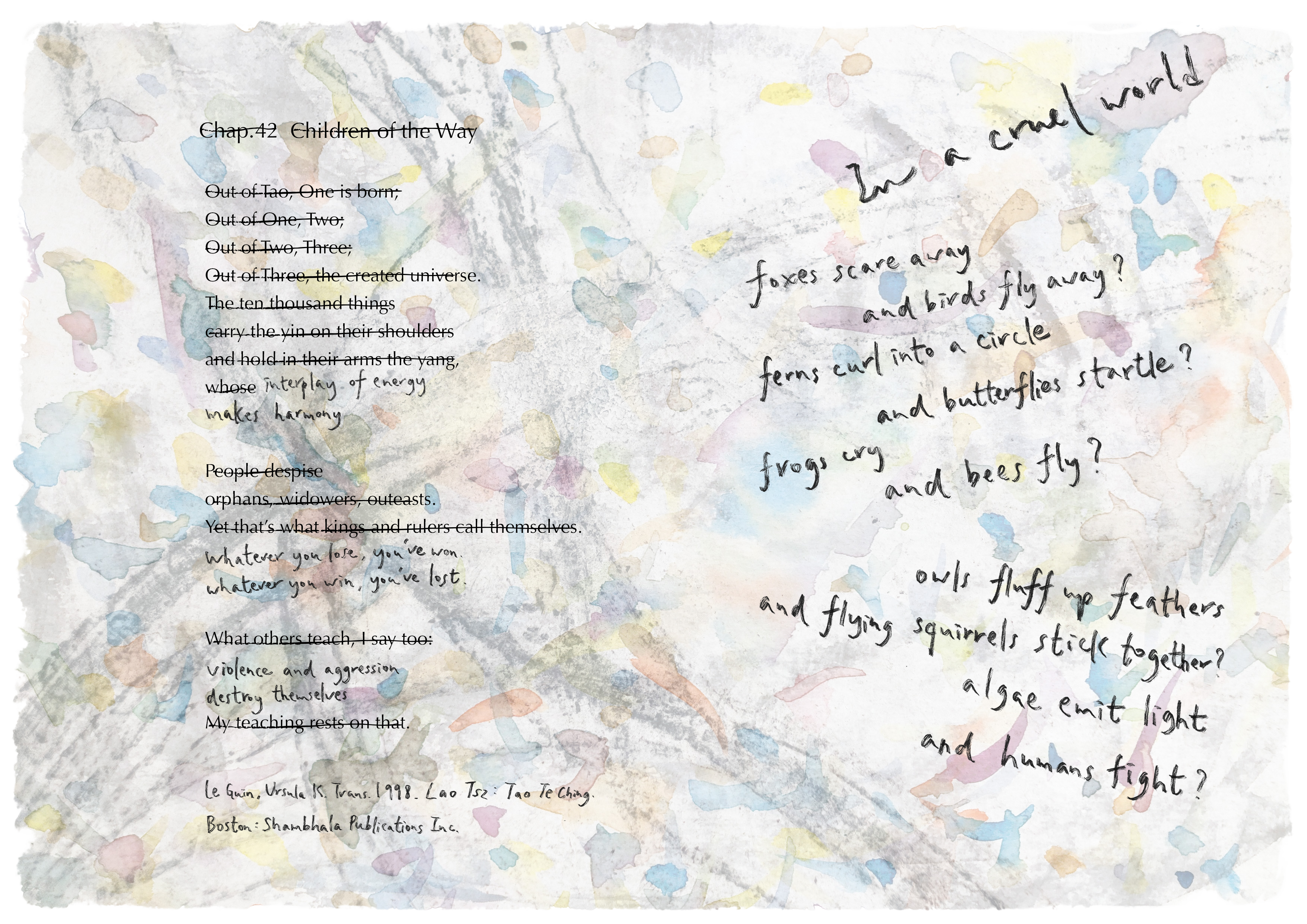

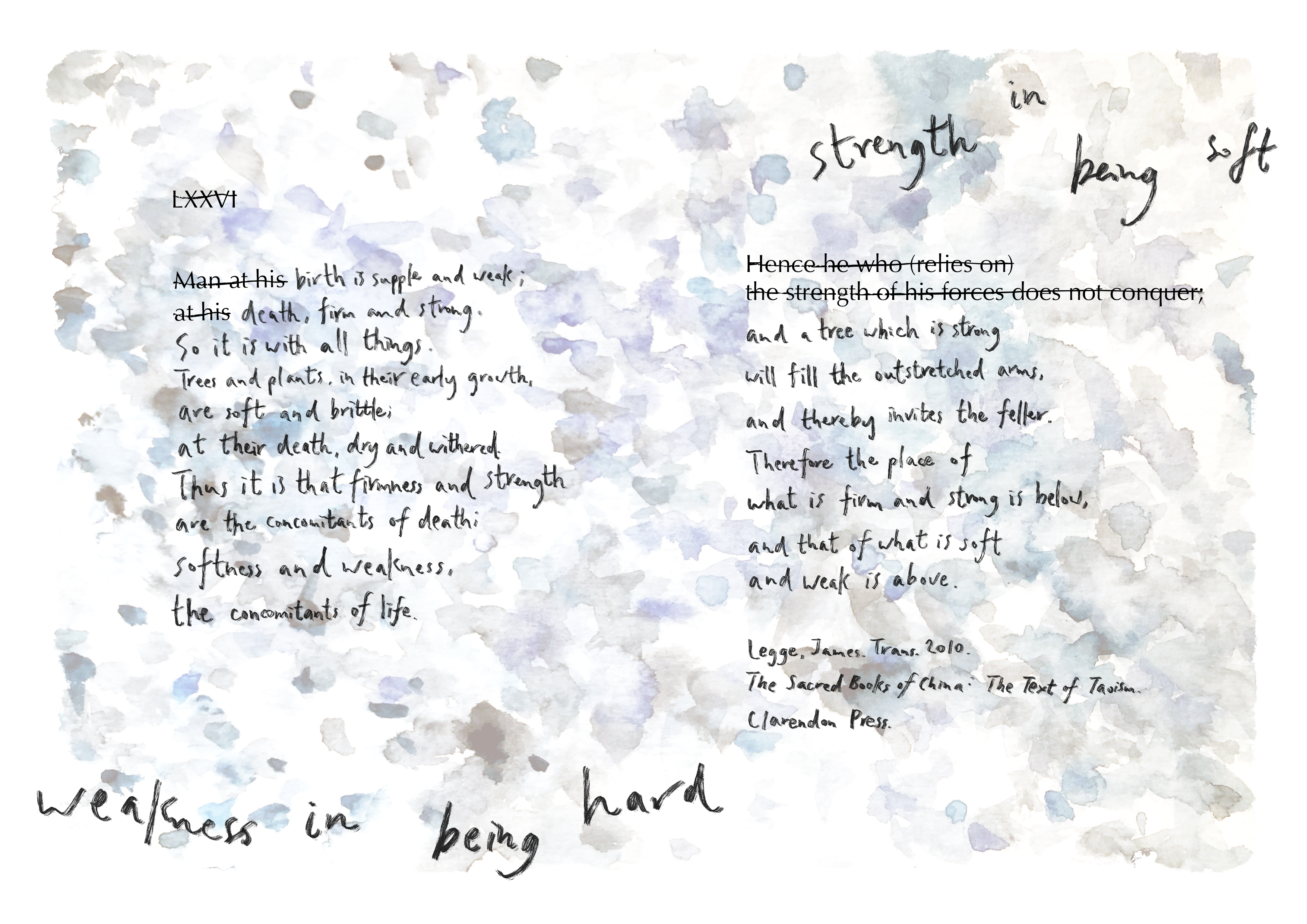

‘Why do you read Daodejing in translation?’ I was asked. I decided to experiment with language thinking by doing multiple forms of translation. I put the first two verses of Daodejing in Ancient Chinese, Cantonese transliteration, and English translation in my text. Following artist André Masson’s concept of automatic drawings, I let the charcoal and watercolour brush wander without conscious control. They have some affinities with ink-wash paintings, which are rhythmic, and emphasise spontaneity, simplicity, and self-expression. The graphic slides will show how I arrived at an idea by writing the translated language, drawing lines across uninspired, human-centric thinking, and creating spaces around words.

I.

I was six

when I first read Daodejing.[1] It was probably not an ideal book for a child.

As a first-time reader, the first

two verses were puzzling but rhythmic.[2]

‘

道可道

非常道

dou6 ho2 dou6

fei1 seung4 dou6

名可名

非常名

ming4 ho2 ming4

fei1 seung4 ming4

’

[1] Daodejing was written around the 6th century in ancient China. In short, it

expresses the Ancient Chinese viewpoint on nature, morals, and politics (Chang

2017, 93-95). The text travelled through Chinese history, evolving alongside

the changes of different dynasties. Following the Scottish missionary John

Chalmers’ first English version in 1868, Daodejing goes through rebirthand rewriting in many locales and times, with each environment impacted

by unique historical, social and cultural contexts (Ibid).

[2] I included the Cantonese pronunciations because Cantonese

is my mother tongue. When I first read the text, I read it aloud.

II.

Much later, something invisible before became visible.[3] The voice of philosophy spoke

to me when I reread the words.

But language can both create and limit thinking

if one is so used to it.

As an experiment, I turned to reading in translations.

Perhaps a different wording can stand outside of the original? [4]

What if the original has no fixed

identity?[5]

The first two verses in the translation

are terse but comprehensive.

‘

Dao called Dao

is not Dao.

Names can name

no lasting name.

’

[3] In The Wisdom of Laotse, the

Chinese philosopher Lin Yutang describes the reaction to reading Daodejing.‘The first reaction of anyone scanning the Book of Tao is laughter; the

second reaction, laughter at one's own laughter; and the third, a feeling that

this sort of teaching is very much needed today (Lin 1958,20).’ Not in a theoretical way, this saying rings

true to me when re-approaching the text.

[4] Through investigating the rewording of Daodejing,

the meaning of dao is correspondingly redefined. In this project journal, I

will focus on deconstructing four translated versions. First, The Sacred

Books of China: The Texts of Taoism, translated

by James Legge (1815-1897), a Scottish sinologist, I find the language he used

belongs to Christian vocabulary. The paratext, for example, ‘Par. 3 suggests

the words of the apostle John, He that loveth not knoweth not God; for God is

love.’ shows the intention to promote the Christian faith (Chang 2017, 95).

Second, Lao

Tzu: Tao Te Ching translated by American novelist

Ursula K. Le Guin, is a rendition of Paul Carus’ edition of 1898 (Le Guin 1998). Unlike most translated

works, Le Guin’s non-hierarchal, unwise version avoided naming Daoist Sages in

the text. Third, Tao Te Ching translated by scholars Stephen Addiss and

Stanley Lombardo is based on the Chinese philosopher Wang Bi edition by

retaining the single monosyllable of Chinese characters and getting rid of

gender specificity (Addiss and Lombardo 1993, xvi). Fourth, The

Wisdom of Laotse translated by Chinese scholar Lin Yutang, is comprised of a

translation of Daodejing and ‘comments’ on the chapter in the text. Lin

notes that he confines himself to an editor’s job of making the connections

clear, and pointing out emphasis here and there, but not expressing his opinion

(Lin 1958, 34).

[5] No one knows the

actual words and form of the ‘original’ Daodejing. The earliest complete

written editions date back

to the early Han dynasty (Michael 2022, 2). While sinologists seek the original

written text, deconstructionists are interested in how the original texts are

rewritten. According to the philosopher Jacques Derrida, The original and its

translations are in symbiotic relationships – mutually supplementing each other, defining and

redefining a phantasm of sameness (Gentzler 1993, 147-149).

III.

How can I think what I do not imagine? How can I hear what words do not

speak?[6]

The first two verses are still here but fluid.

‘

道可道

非常道

dou6 ho2 dou6

fei1 seung4 dou6

Dao called Dao

is not Dao.

名可名

非常名

ming4

ho2 ming4

fei1 seung4 ming4

Names can name

no lasting name

’

[6] For the

poet and critic Ezra Pound, Chinese characters represent things in

action, in progress, things with energy, and their form (Gentzler

1993, 18). All words are signs similar to Chinese characters that are changing,

newly created and capable of being metamorphosised (Ibid). I

am struck by Ezra’s interpretation of language because the flowing notion of

languages resonates with the dynamic, ongoing nature of Daoist cosmology.

Images:

Charcoal, lichen drawings, MA Art and Ecology Degree Show 2023, Goldsmiths,

University of London.

Photography:

Ruby Christian.