Barney Pau

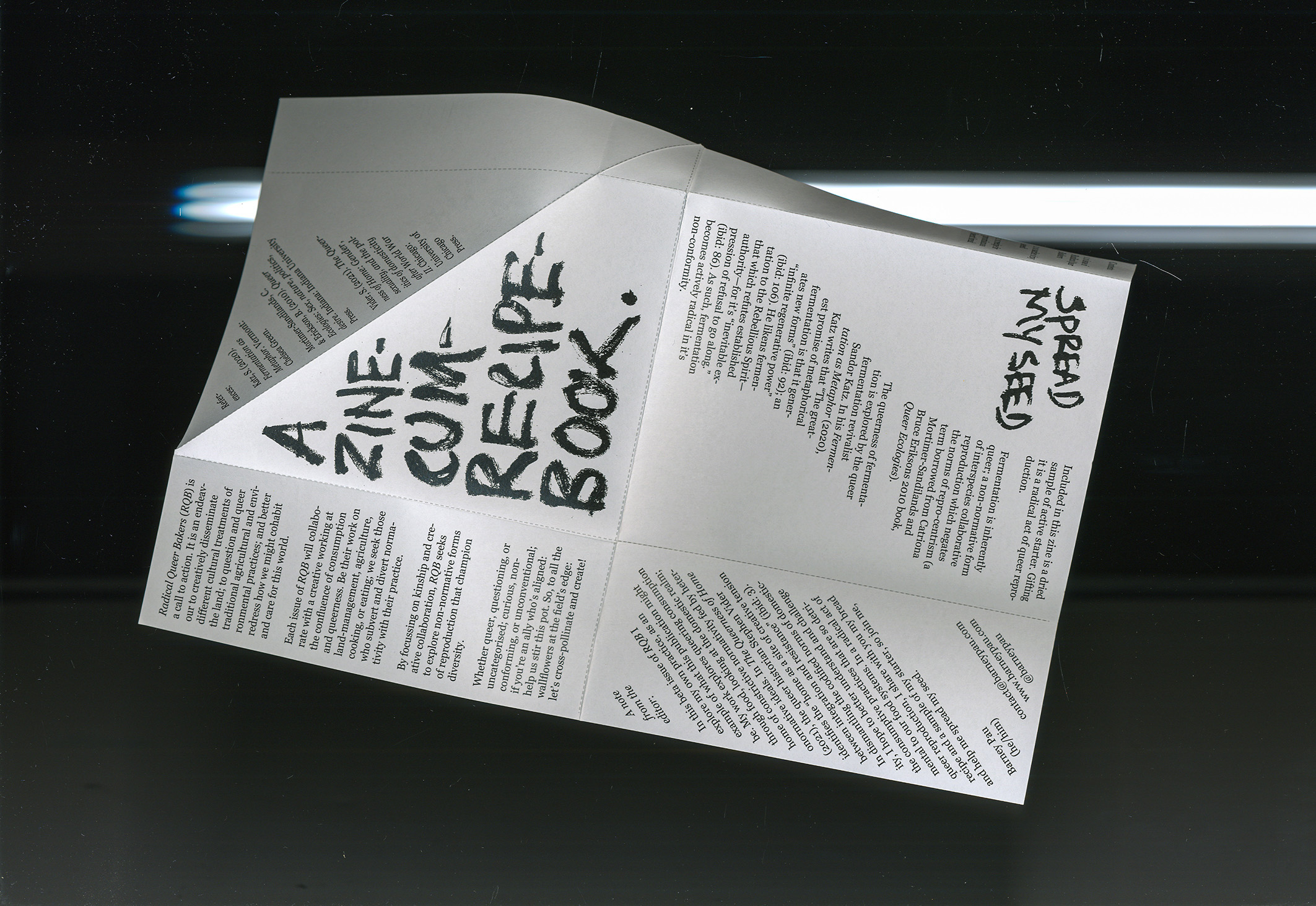

Radical Queer

Bakers

A

Zine-Cum-Recipe-Book

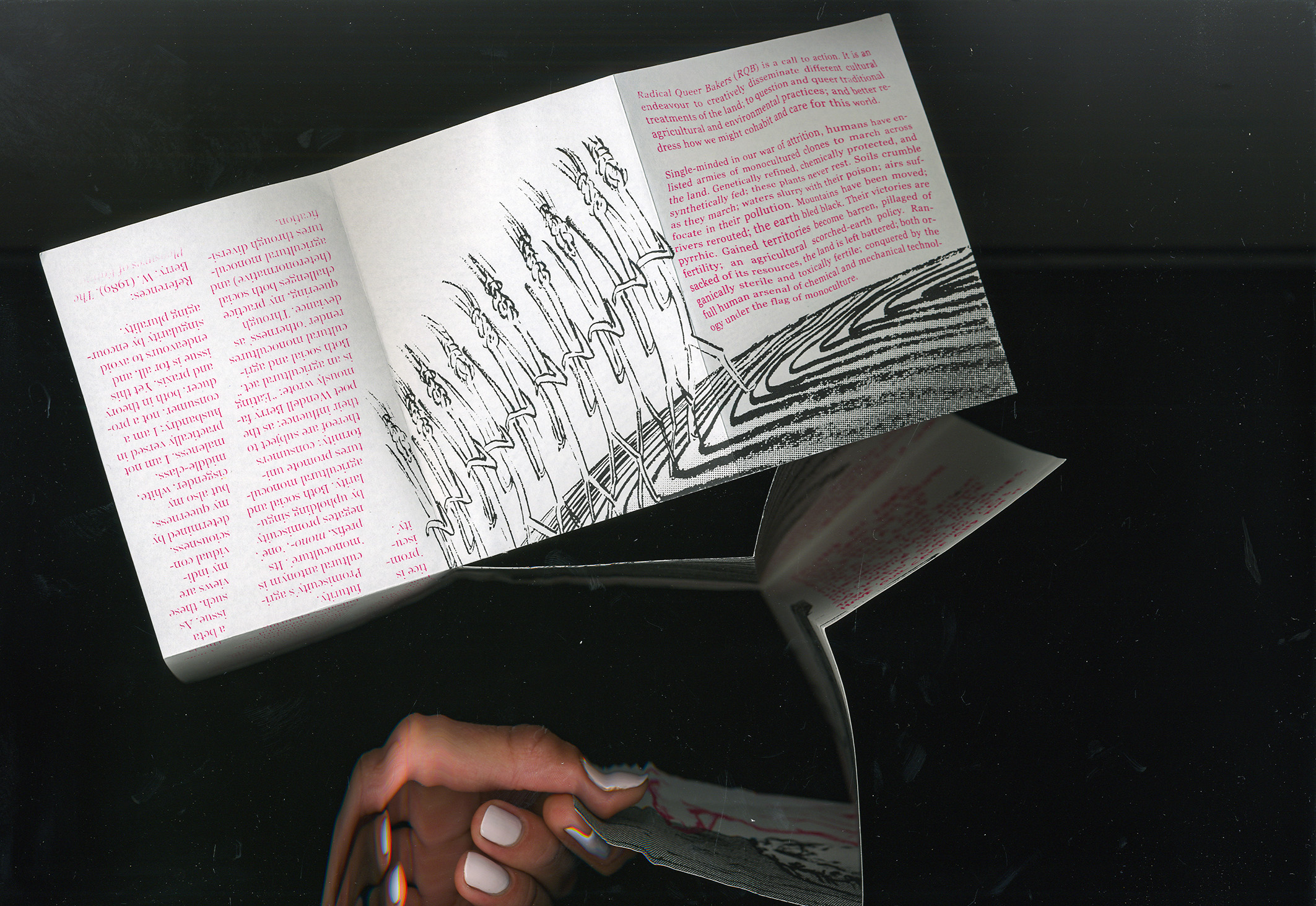

Single-minded in our war of attrition, humans have enlisted armies of monocultured clones to march across the land. Genetically refined, chemically protected, and synthetically fed; these plants never rest. Soils crumble as they march; waters slurry with their poison; airs suffocate in their pollution. Mountains have been moved; rivers rerouted; the earth bled black. Their victories, however, are pyrrhic. Gained territories become barren, pillaged of fertility; an agricultural scorched-earth policy. Ransacked of its resources, the land is left battered; at once organically sterile and toxically fertile; conquered with the full human arsenal of chemical and mechanical technology under the unifying flag of monoculture.

Radical Queer Bakers(RQB) is a call to action. It is an endeavour to creatively disseminate conventional treatments of the land; to question and queer traditional agricultural and environmental practices; and better redress how we might cohabit and care for this world.

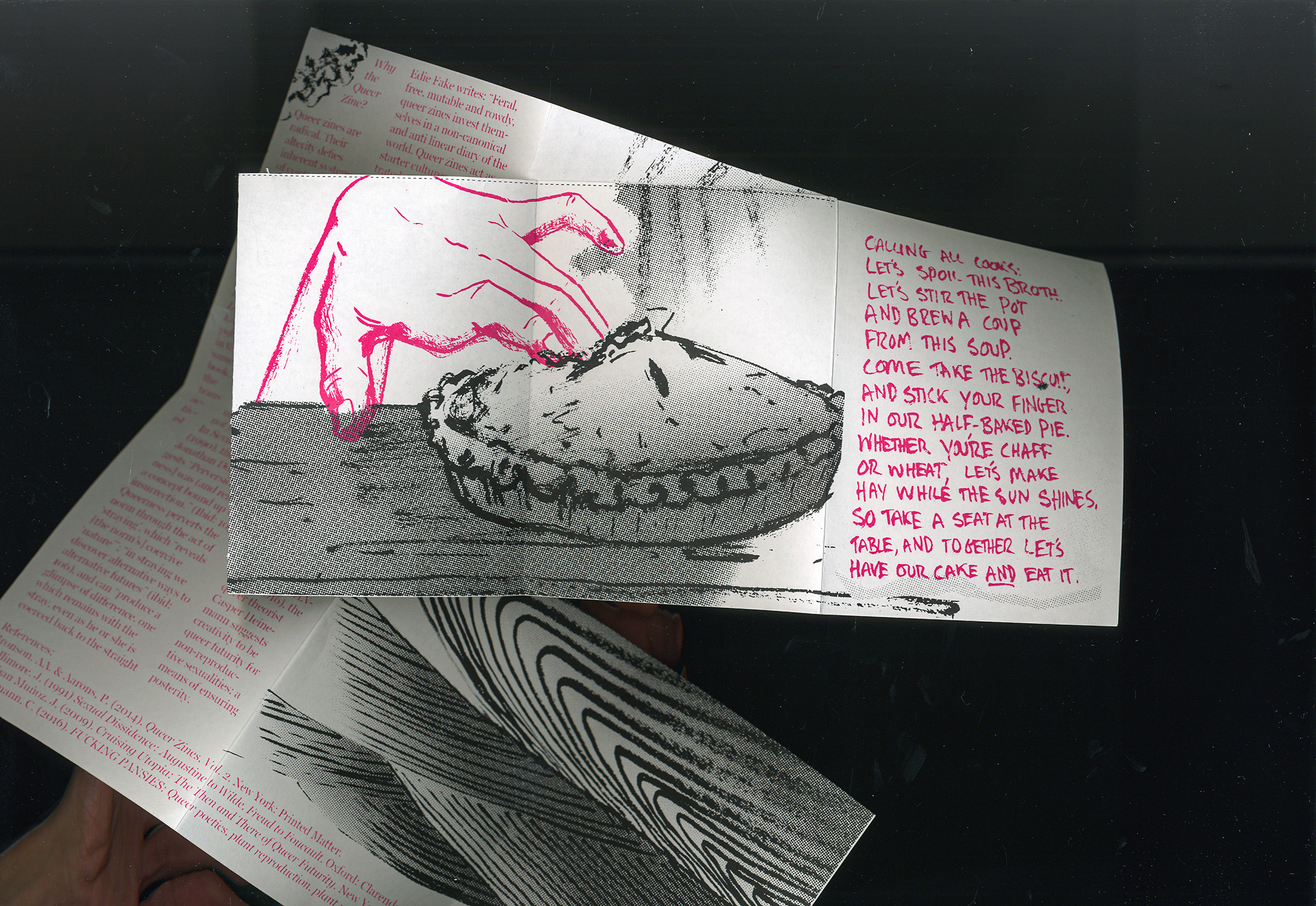

RQB calls all cooks: let’s spoil this broth. Let’s stir the pot and brew a coup from this soup. Come take the biscuit, and stick your fingers in our half-baked pie. Whether you’re chaff or wheat, let’s make hay while the sun shines. So take a seat at the table, and together let’s have our cake and eat it.

Each issue of RQB will collaborate with a creative who works at the confluence of consumption and queerness. Whether their work focuses on land-management, agriculture, cooking, or eating; we seek those who subvert and divert normativity with their practice. By focussing on kinship and creative collaboration, RQB seeks to explore non-normative forms of reproduction that champion diversity.

Whether queer, questioning, or uncategorised; curious, non-conforming, or unconventional; if you’re an ally who’s aligned: help us stir this pot. So, to all the wallflowers at the field’s edge: let’s cross-pollinate and create!

A note from the editor:

In this beta issue of RQB I explore my own practice, as an example of what this publication might be. As such, these views are my individual consciousness, determined by my queerness, but also by my cisgender, white, middle-class, maleness. I am not practically versed in husbandry; I am a consumer, not a producer, both in theory and praxis. Yet this issue is for all, and endeavours to avoid singularity by encouraging plurality.

My work explores queering consumption through food, looking at the domestic realm; home of constrictive normativity fed by heteronormative ideals. In The Queerness of Home (2021), the queer historian Stephen Vider identifies the “home as a site of creative tension between integration and resistance” (ibid: 3). In dismantling the codified norms of domesticity, I hope to better understand and challenge the consumptive practices that are so detrimental to our food systems. In a radical act of queer reproduction, I share with you my bread recipe and a sample of my starter, so join me, and help me spread my seed.

Situating myself

Sexuality—queer or not—is often demonised, and non-reproductive sex deemed superfluous. Queerness, in it’s non-reproductivity and sexual alterity to the (hetero)norm, is doubly condemned. Liberation movements often use sexuality to defy inherent structures of power. My work sexualises and queers to explore alternatives to normativity.

One particularly pertinent word to my practice is ‘promiscuity’. ‘Promiscuous’, from Latin promiscuus: ‘indiscriminate’, is based on miscere: ‘to mix’, and originally meant ‘consisting of elements mixed together’; whence contemporary notions of ‘indiscriminate sex’ derivate. Promiscuity is diversity through freedom of choice. In agriculture, a promiscuous crop genetically self-diversifies, creating a ‘population’ of similar, yet genetically unique plants. This engenders self-sufficiency: if one species senescences to an abiotic stress—pest, disease, weather—another is adapted to survive. Populations are environmental failsafes, ensuring futurity.

Promiscuity’s agricultural antonym is ‘monoculture’. Its prefix, mono-, ‘one’, negates promiscuity by upholding singularity. Both social and agricultural monocultures promote uniformity: consumers thereof are subject to their influence; as the poet Wendell Berry famously wrote: “Eating is an agricultural act.” Both social and agricultural monocultures render ‘otherness’ as deviance. Through queering, my practice challenges both social (heteronormative) and agricultural monocultures through diversification.

Sexuality—queer or not—is often demonised, and non-reproductive sex deemed superfluous. Queerness, in it’s non-reproductivity and sexual alterity to the (hetero)norm, is doubly condemned. Liberation movements often use sexuality to defy inherent structures of power. My work sexualises and queers to explore alternatives to normativity.

One particularly pertinent word to my practice is ‘promiscuity’. ‘Promiscuous’, from Latin promiscuus: ‘indiscriminate’, is based on miscere: ‘to mix’, and originally meant ‘consisting of elements mixed together’; whence contemporary notions of ‘indiscriminate sex’ derivate. Promiscuity is diversity through freedom of choice. In agriculture, a promiscuous crop genetically self-diversifies, creating a ‘population’ of similar, yet genetically unique plants. This engenders self-sufficiency: if one species senescences to an abiotic stress—pest, disease, weather—another is adapted to survive. Populations are environmental failsafes, ensuring futurity.

Promiscuity’s agricultural antonym is ‘monoculture’. Its prefix, mono-, ‘one’, negates promiscuity by upholding singularity. Both social and agricultural monocultures promote uniformity: consumers thereof are subject to their influence; as the poet Wendell Berry famously wrote: “Eating is an agricultural act.” Both social and agricultural monocultures render ‘otherness’ as deviance. Through queering, my practice challenges both social (heteronormative) and agricultural monocultures through diversification.

What’s in a name?

Radical: The term 'radical’ is rooted in late Middle English to mean ‘forming the root’ and ‘inherent’; in turn sourced from late Latin radicalis, from radix; radic-: ‘root’. Radicalism is a literal reconnection to one’s roots.

Queer: The term ‘queer’ comes from the Low German queer: ‘off-centre’; taken from the Old High German twerh: ‘oblique’, which in turn is rooted in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) terkw: ‘to twist’. ‘Queer’ entered 16th century English to mean ‘strange’, ‘odd’, or ‘peculiar’. By the 19th century queer had become a pejorative term for sexual deviance. A century later it was reclaimed by queer activists who turned it into a homophile term, and has since become an umbrella term for non-heterosexuals. By the 1990s queer theory became recognised in academia as a critical discourse against heteronormativity, and ‘queering’ as an action, joined ‘queer’ as an identity.

Baker: In Western narratives, bread is synonymous with sustenance. Through its medium we can understand culture: from its contextual import; and entwined history with agriculture; to the infrastructural problems it incurs; and the potential solutions it presents. The baker is thus a conduit: they form and shape the way we eat; their ferments can foment us; and into their bread messages of responsible consumption can be baked.

Why the Queer

Zine?

Queer zines are radical. Their alterity defies inherent systems of control. The introduction to Queer Zines Vol. 2 (2014) states that “queer zines [...] establish communality in difference.” (ibid: 4). In Fruity Zine Love Poem Essay, published in the same book, the trans activist Edie Fake writes: “Feral, free, mutable and rowdy, queer zines invest themselves in a non-canonical and anti linear diary of the world. Queer zines act as starter cultures—concentrated, restless doses of fevered activity” (ibid: 204).

What is Queering?

Queering is a practice as much as queerness is an identity. Both are based in alterity. Queering is subversion; perversion; divergence from the norm. In Cruising Utopia (2009), the queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz writes: “Queerness is an ideality”; “a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present”. Muñoz presents queerness as futurity; a utopia to strive for, though not yet achieved. The philosopher Jonathan Dollimore suggests in Sexual Dissidence (1990) that “Perversion [queerness] was (and remains) a concept bound up with insurrection.” (Ibid: 103). He writes that queerness perverts the norm through the act of ‘straying’, which “reveals [the norm’s] coercive ‘nature’”; “in straying we discover alternative ways to alternative futures” (ibid: 106), and can “produce a glimpse of difference, one which remains with the stray, even as he or she is coerced back to the straight and narrow” (ibid: 107). Queerness, by ‘straying’ from the norm, enables alterity. In their article FUCKING PANSIES (2016), the queer theorist Casper Heinemann suggests creativity to be queer futurity for non-reproductive sexualities; a means of ensuring posterity.

Queer zines are radical. Their alterity defies inherent systems of control. The introduction to Queer Zines Vol. 2 (2014) states that “queer zines [...] establish communality in difference.” (ibid: 4). In Fruity Zine Love Poem Essay, published in the same book, the trans activist Edie Fake writes: “Feral, free, mutable and rowdy, queer zines invest themselves in a non-canonical and anti linear diary of the world. Queer zines act as starter cultures—concentrated, restless doses of fevered activity” (ibid: 204).

What is Queering?

Queering is a practice as much as queerness is an identity. Both are based in alterity. Queering is subversion; perversion; divergence from the norm. In Cruising Utopia (2009), the queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz writes: “Queerness is an ideality”; “a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present”. Muñoz presents queerness as futurity; a utopia to strive for, though not yet achieved. The philosopher Jonathan Dollimore suggests in Sexual Dissidence (1990) that “Perversion [queerness] was (and remains) a concept bound up with insurrection.” (Ibid: 103). He writes that queerness perverts the norm through the act of ‘straying’, which “reveals [the norm’s] coercive ‘nature’”; “in straying we discover alternative ways to alternative futures” (ibid: 106), and can “produce a glimpse of difference, one which remains with the stray, even as he or she is coerced back to the straight and narrow” (ibid: 107). Queerness, by ‘straying’ from the norm, enables alterity. In their article FUCKING PANSIES (2016), the queer theorist Casper Heinemann suggests creativity to be queer futurity for non-reproductive sexualities; a means of ensuring posterity.

Why do we look

like we do?

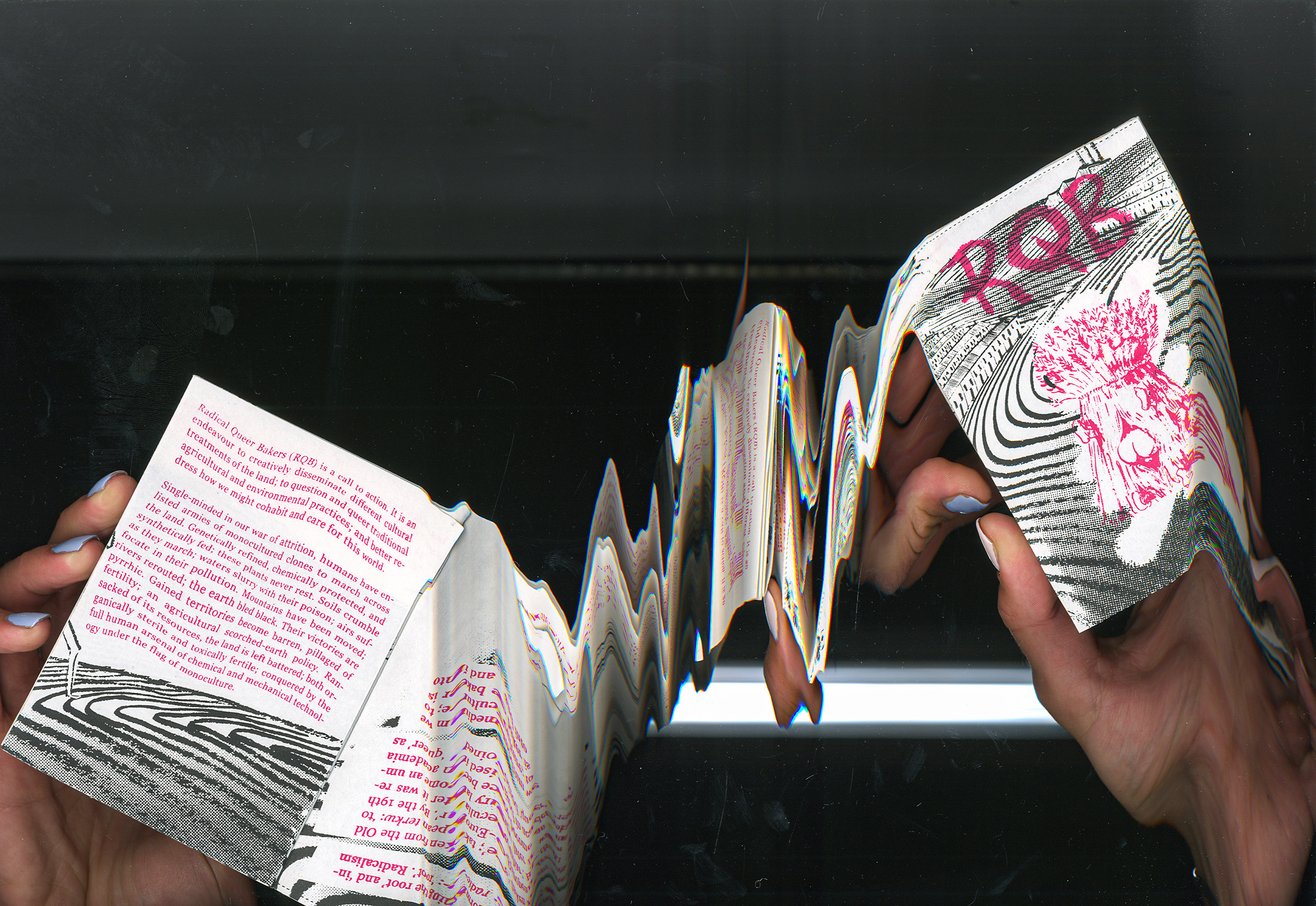

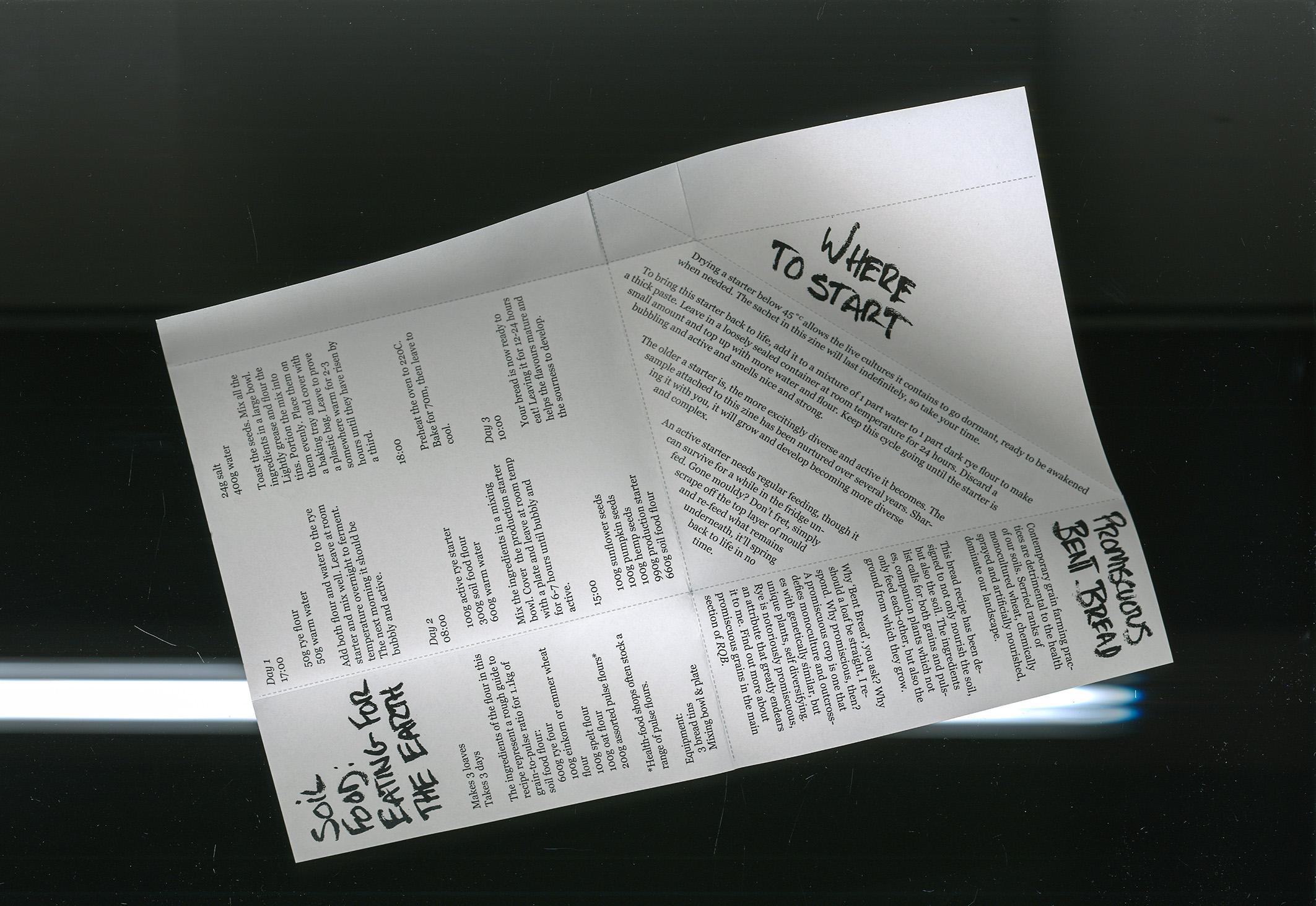

This zine takes a ‘boustrophedon structure’; a method of book-making where the entire publication is made of one whole sheet of paper. Boustrophedon is an ancient style of writing in which alternate lines are written in reverse, used before the widespread adoption of contemporary conventional writing styles, in which lines begin on the same side. The term comes from Ancient Greek: βουστροφηδόν [boustrophēdón]: composed of βοῦς [bous], “ox”; στροφή [strophḗ], “turn”; and the suffix -δόν, [-dón], “like”. Brought together, the term literally means “like the ox turns [while ploughing]”.

By Adopting this approach, each page of RQB represents part of a united whole—a bigger picture, if you will. The publications’ non-linear, plural trajectories negate the page order of conventional publishing.

Similarly, much as furrows regulate a field’s format, the gridwork of traditional typography can constrict creativity. By obfuscating the rigidity of traditionally gridded typographic layouts, RQB queers convention and promotes alterity, while still adhering to a print-inspired format.

This zine takes a ‘boustrophedon structure’; a method of book-making where the entire publication is made of one whole sheet of paper. Boustrophedon is an ancient style of writing in which alternate lines are written in reverse, used before the widespread adoption of contemporary conventional writing styles, in which lines begin on the same side. The term comes from Ancient Greek: βουστροφηδόν [boustrophēdón]: composed of βοῦς [bous], “ox”; στροφή [strophḗ], “turn”; and the suffix -δόν, [-dón], “like”. Brought together, the term literally means “like the ox turns [while ploughing]”.

By Adopting this approach, each page of RQB represents part of a united whole—a bigger picture, if you will. The publications’ non-linear, plural trajectories negate the page order of conventional publishing.

Similarly, much as furrows regulate a field’s format, the gridwork of traditional typography can constrict creativity. By obfuscating the rigidity of traditionally gridded typographic layouts, RQB queers convention and promotes alterity, while still adhering to a print-inspired format.

Promiscuous Bent Bread

The bread recipe included in this zine has been designed to not only nourish the soul, but also the soil. The ingredients list calls for both grains and pulses, companion plants which not only feed each-other, but also the ground from which they grow. “Why ‘Bent Bread’?”, you ask? “Why should a loaf be straight?”, I respond. “Why promiscuous, then?” As previously mentioned, a promiscuous crop is one that defies monoculture and outcrosses with genetically similar, but unique plants, effectively self diversifying.

Why rye?

Rye is notoriously promiscuous, an attribute that greatly endears it to me, hence my preference to baking with it. Rye bread need not be kneaded, requiring less intervention and granting the cultures that inhibit it greater autonomy.

Rye is also inherently queer. The domestication of rye occurred somewhat differently to that of other grains. Wild rye, a grass similar to wild wheat, entered the field as a weed; undesired by the farmer. With each harvest, the farmer would select the most desirable wheat of their crop and plant it the next year. The rye that acted and looked most similar to the wheat would also get selected by the unsuspecting farmer, securing itself another generation of husbandry. This is a process called Vavilovian mimicry, and involves three agents: the model, the mimic, and the dupe. Rye, by mimicking wheat—the model—dupes the human. Rye underwent a series of morphological, physiological, and behavioural changes in this process of assimilation, becoming an unintentional domesticate.

Thus, due to these promiscuous, anti-assimilationist tendencies, rye continues to fight the homogeneity of standardisation and reductionism; it is radically queer in it’s refusal to go along; it ‘strays’. Similar, but never truly the same; forced to assimilate, yet fighting for agency: rye’s parities with queer identity make it an apposite grain to bake with.

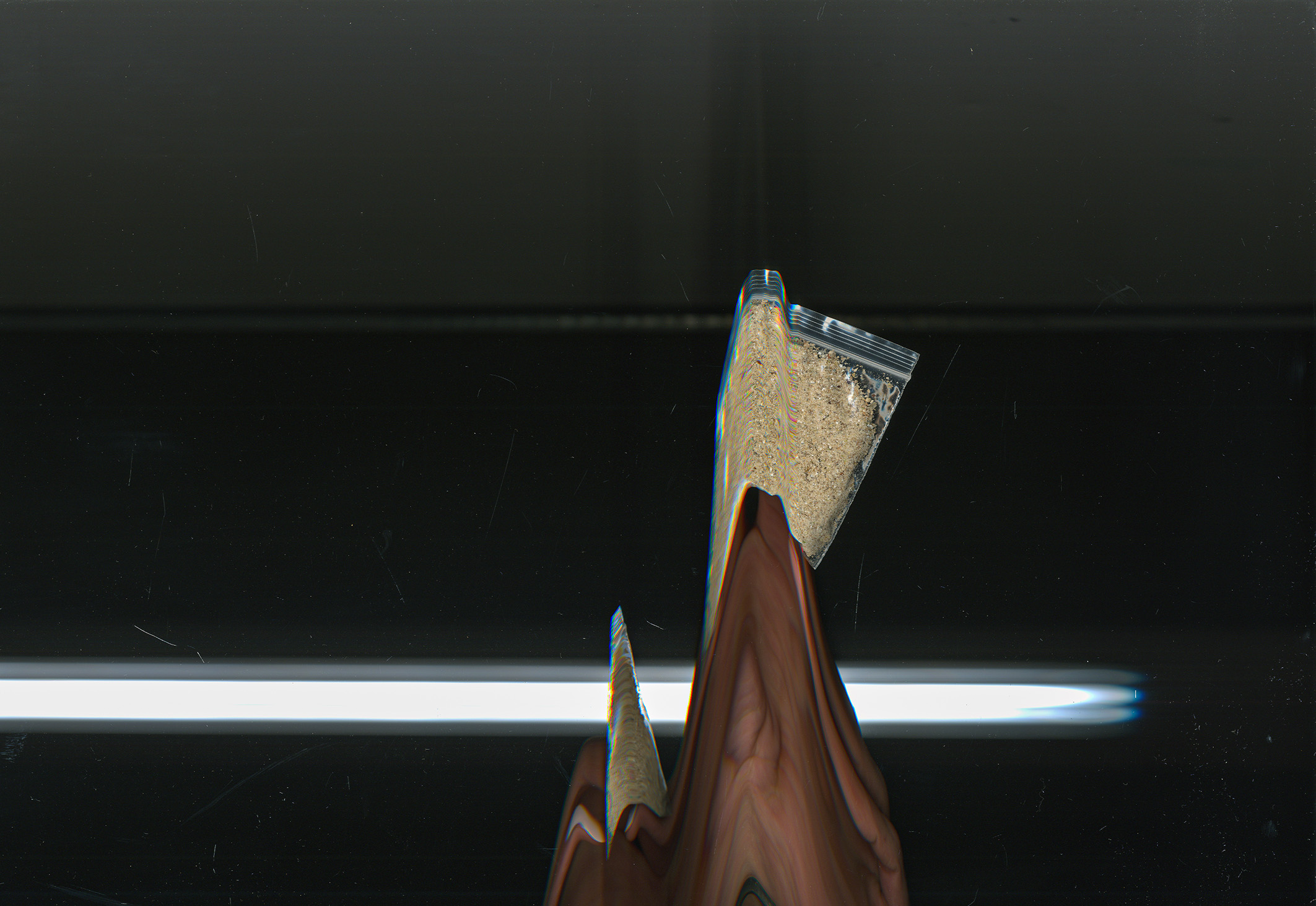

Spread my Seed

Included in this zine is a dried sample of active starter. Gifting it is a radical act of queer reproduction. Fermentation is inherently queer; a non-normative form of interspecies collaborative reproduction which negates the norms of repro-centrism (a term borrowed from Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Eriksons 2010 book, Queer Ecologies). The queerness of fermentation is explored by the queer fermentation revivalist Sandor Katz. In his Fermentation as Metaphor (2020), Katz writes that “The greatest promise of metaphorical fermentation is that it generates new forms” (ibid: 92); it is an “infinite regenerative power” (ibid: 106). He likens fermentation to the Rebellious Spirit—they who refute established authority—for its “inevitable expression of refusal to go along.” (ibid: 86). Fermentation thus becomes actively radical in its non-conformity.

Included in this zine is a dried sample of active starter. Gifting it is a radical act of queer reproduction. Fermentation is inherently queer; a non-normative form of interspecies collaborative reproduction which negates the norms of repro-centrism (a term borrowed from Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Eriksons 2010 book, Queer Ecologies). The queerness of fermentation is explored by the queer fermentation revivalist Sandor Katz. In his Fermentation as Metaphor (2020), Katz writes that “The greatest promise of metaphorical fermentation is that it generates new forms” (ibid: 92); it is an “infinite regenerative power” (ibid: 106). He likens fermentation to the Rebellious Spirit—they who refute established authority—for its “inevitable expression of refusal to go along.” (ibid: 86). Fermentation thus becomes actively radical in its non-conformity.

Where to start

Drying a starter below 45˚C, as it has been prepared here, allows the live cultures it contains to go dormant, ready to be awakened when needed. The sachet in this zine will last indefinitely, so take your time.

To bring this starter back to life, add it to a mixture of 1 part water to 1 part dark rye flour to make a thick paste. Leave in a loosely sealed container at room temperature for 24 hours. Discard a small amount and top up with more water and flour. Keep this cycle going until the starter is bubbling and active and smells nice and strong. An active starter needs regular feeding, though it can survive for a while in the fridge unfed. Gone mouldy? Don’t fret, simply scrape off the top layer of mould and refeed what remains underneath, and it’ll bubble back to life in no time.

The older a starter is, the more excitingly diverse and active it becomes. The sample attached to this zine has been nurtured over several years. By sharing it with you it will grow and develop becoming more diverse and complex.

Soil Food: Eating for the Earth

Makes 3 loaves

Takes 3 days

The ingredients of the flour in this recipe represent a rough guide to grain-to-pulse ratio for 1.1kg of soil food flour:

600g rye four

100g einkorn or emmer wheat flour=

100g spelt flour

100g oat flour

200g assorted pulse flours*

*Health-food shops often stock a range of pulse flours.

Equipment:

3 bread tins

Mixing bowl & plate

Day 1

17:00

50g rye flour

50g warm water

Add both flour and water to the rye starter and mix well. Leave at room temperature overnight to ferment. The next morning it should be bubbly and active.

Day 2

08:00

100g active rye starter

300g soil food flour

600g warm water

Mix the ingredients in a mixing bowl. Cover the production starter with a plate and leave at room temp for 6-7 hours until bubbly and active.

15:00

100g sunflower seeds

100g pumpkin seeds

100g hemp seeds

990g production starter

660g soil food flour

24g salt

400g water

Toast the seeds. Mix all the ingredients in a large bowl. Lightly grease and flour the tins. Portion the mix into them evenly. Place them on a baking tray and cover with a plastic bag. Leave to prove somewhere warm for 2-3 hours until they have risen by a third.

18:00

Preheat the oven to 220C. Bake for 70m, then leave to cool.

Your bread is now ready to eat! Leaving it for 12-24 hours helps the flavours mature and the sourness to develop.

Edited and designed by Barney Pau (he/him) during his studies on the MA Art & Ecology at Goldsmiths, University of London. For more information visit the following barneypau.com / contact@barneypau.com / @barneypau

References:

Berry, W. (1989). The Pleasures of Eating.

Bronson, AA. & Aarons, P. (2014). Queer Zines, Vol. 2. New York: Printed Matter.

Dollimore, J. (1991) Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Esteban Muñoz, J. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009). New York: NYU Press.

Heinemann, C. (2016). FUCKING PANSIES: Queer poetics, plant reproduction, plant poetics, queer reproduction.

Katz, S. (2020). Fermentation as Metaphor. Vermont: Chelsea Green.

Mortimer-Sandilands, C. & Erickson, B. (2010). Queer Ecologies: Sex, nature, politics, desire. Indiana: Indiana University

Vider, S. (2021). The Queer- Press. ness of Home: Gender, sexuality, and the politics of domesticity after World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berry, W. (1989). The Pleasures of Eating.

Bronson, AA. & Aarons, P. (2014). Queer Zines, Vol. 2. New York: Printed Matter.

Dollimore, J. (1991) Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Esteban Muñoz, J. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009). New York: NYU Press.

Heinemann, C. (2016). FUCKING PANSIES: Queer poetics, plant reproduction, plant poetics, queer reproduction.

Katz, S. (2020). Fermentation as Metaphor. Vermont: Chelsea Green.

Mortimer-Sandilands, C. & Erickson, B. (2010). Queer Ecologies: Sex, nature, politics, desire. Indiana: Indiana University

Vider, S. (2021). The Queer- Press. ness of Home: Gender, sexuality, and the politics of domesticity after World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.