Sophie Mayer

BEING BUTCH IN COAL COUNTRY

The Oxford Dictionary states matter of fact that coal is 'carbonized plant matter used as fuel’ as if energy is the primary reason for existence. This definition of coal is the progeny of an extractive, exploitative, capitalist gaze. This hetero-normative definition of Coal is where my research begins to inspire more questions. How do we deal with structures of inheritance rooted in the past? Building on Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s queer performativity as an ongoing project for transforming the way we may define—and break—boundaries, my research aims to contribute to the limited ontologies surrounding this fleshy inheritance and dark matter we call coal.

We should be able to open the Oxford dictionary and find that the 'noun' Coal is no longer defined as fuel, but rather as an adjective / heterogeneous / matter / ancestor / butch-trans-materiality(1) / remediator in which there are a variety of ongoing, mutable fizzes and connections between multiple species, and series of entanglements of coming into being, a metabolic mutualism not yet appreciated by a late capitalist society.

![]() Coal Degradation Study over 12 months in Walled Garden

Coal Degradation Study over 12 months in Walled Garden

SPACE

“One is not born, one becomes an undutiful daughter.” (2) – Rosi Braidotti

Johannesburg. Jozi. Jo’burg. Joeys. More recently known as Gauteng. Some call it Mshishi, or Kwandonga Ziyaduma (where the walls rumble). The elders call it Shishisburg. Once it was called Egoli. The city quite literally built on top of gold, diamonds, steel, and coal. It sits on one of the largest deposits of precious metal in the world. Arguably one of the biggest cities not built on a major river or port - nothing to see here except highways and mine dumps and dust and passes which curve ever outwards towards the Congo basin.

![]() Vintage Postcard of Johannesburg which explains the modern architecture above a labyrinth of surrounding mine sites – some at a depth of more than 3200m – having two distinct landmarks in the 269m J.G Strijdom Tower and distant 235m Brixton Tower. Photo: John Hone

Vintage Postcard of Johannesburg which explains the modern architecture above a labyrinth of surrounding mine sites – some at a depth of more than 3200m – having two distinct landmarks in the 269m J.G Strijdom Tower and distant 235m Brixton Tower. Photo: John Hone

The flyover city. The African continents ‘big apple’. Also known as the frontier town. A part of the wild west for the roughnecks and the lawless. More brothels than beer halls. A dense, post-apocalyptic air, with a heady mix of blade runner meets London or Bogota, the city known for its grime, crime and protest. There is a whiff of anarchy mixed with resistance, much of the streets crawl with gangsters and tstosis, everyone you knew had personal knowledge of someone who died violently. Yet there remains an indisputable energy and buzz in the cosmopolitan city, attracting thousands of newcomers to the city every day.

The lure of making it big in the city goes back hundreds of years. Johannesburg, with Dar Es Salaam, Nairobi and Addis Ababa are some of the cities with the longest history of human habitation. Longer than Athens, Rome, or Cairo.

Gold was discovered in Johannesburg in 1886, leading to a rush that attracted gold diggers, labourers, shopkeepers, and others from all over what was soon to become known as South Africa. The areas around the mines urbanized rapidly. Within 10 years of the mineral’s discovery Joburg had become South Africa’s largest metropolitan city. This dusty mining town has some of the highest quality anthracite in the world. South African Anthracite is a hard, jet black form of coal prized by the metals industry because of its high carbon and low ash content.

![]() A Mine Dump near Viscount Road, Main Reef Road, Randfontein Johannesburg (2013). Photo: Jason Larkin

A Mine Dump near Viscount Road, Main Reef Road, Randfontein Johannesburg (2013). Photo: Jason Larkin

In the 1800s a new shipment of Europeans cut links with Holland and the Dutch East India Trading Route, breaking inland and calling themselves Afrikaners, after the continent. Originally farmers in the Cape Colony, they migrated to Johannesburg and Pretoria to became miners and traders. They formed a republic, called Die Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek, but were defeated by the British in 1902. South Africa as a political body, is a new one, created by the British and named The Act of Union of 1909. The Afrikaaners main political body party won the white election in 1948 and changed the existing colonial practice of separation of racial groups into a rigid ideology called apartheid*.

*The word apartheid literally means “apartness” or separate in Afrikaans, and more recently has been used in the Israel and Palestinian context.

![]() Apartheid Bench, Johannesburg. Photograph from Author’s archive (1996)

Apartheid Bench, Johannesburg. Photograph from Author’s archive (1996)

While apartheid in South Africa was formalized in law in the late 1940s, the seeds for its creation were established years beforehand. The mining industry impelled the creation of laws and practices in South Africa which progressively disenfranchised the country’s indigenous peoples. Laws such as The Mines and Works Act (1911) effectively excluded blacks from skilled labour in the mines by stipulating that certificates of competency for skilled trades in the mines could only be issued to whites. These “colour bar” laws were engineered to prevent black workers from competing with white workers for the higher-paid jobs. This combination of punitive taxes and other laws and measures artificially induced black unemployment and restricted blacks’ job mobility, creating a supply of readily available cheap labour for the mines. This was effectively developed into an industrial system of exploitation and ideology of apartheid. Forced segregation and the destruction of communities followed. The mostly black and bohemian quarter, SophiaTown, was replaced with an all-white suburb called Triomf.

By 1958, Hendrik Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid became Prime Minister and Nelson Mandela was being tried for treason in the old Johannesburg Drill Hall. The revenues from gold and coal sustained the pariah apartheid regime after 1961 in the face of economic sanctions and military spending. For decades, anti-apartheid resistance grew, the eventual liberation of the people came in 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from serving a twenty-seven-year sentence on Robben Island in Cape Town.

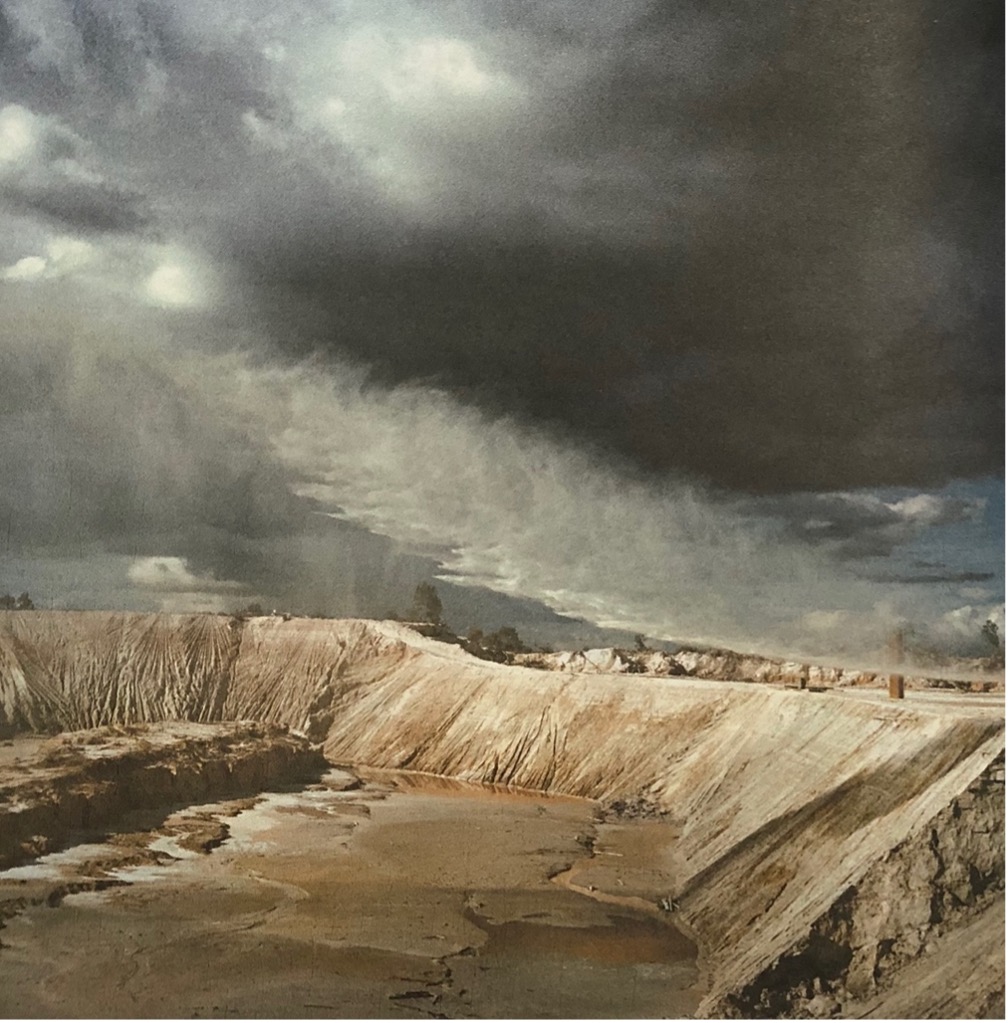

![]() Umlalazi in Natal, South Africa (2019.) This mine is owned by Anglo American. Umlalazi is a 250tph modular coal processing plant. The plant can produce both high-grade and low-grade coal using a 3 product Cyclone. The plant can produce 120 000 tons of coal per month.

Umlalazi in Natal, South Africa (2019.) This mine is owned by Anglo American. Umlalazi is a 250tph modular coal processing plant. The plant can produce both high-grade and low-grade coal using a 3 product Cyclone. The plant can produce 120 000 tons of coal per month.

It was the same year my father took me to the mines in Witbank for the first time; to witness large grey mounds of broken ground, bare tree stumps and trailing's of slurry and liquid which stuck to my shoes and fingers, staining them a dark black colour. The materiality of the fleshy dark substance appeared mutable, contingent, in a constant state of being and becoming. Beneath my feet was the geo-trauma of a mineralogical extraction site. I pick out the colours along the bank: red for iron, white for sulphur, green for copper, yellow for uranium. In my nostrils, the stench of burnt matches, skunk, and rotten eggs. Energy becoming material in this dark alterity.

![]() This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralized acid mine drainage. Even after neutralization, this ever-growing, sludge-and-water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copper and cobolt. (2013) Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein Photo: Jason Larkin

This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralized acid mine drainage. Even after neutralization, this ever-growing, sludge-and-water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copper and cobolt. (2013) Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein Photo: Jason Larkin

The toxic result of over 150 years of irresponsible mining, there are currently estimated to be around 700 abandoned mine dumps with 600,000 metric tonnes of radioactive uranium buried in waste rock in and around Johannesburg. Making it undoubtedly the most uranium-contaminated city in the world according to Antony Turton, from the University of Free State’s Centre for Environmental Management.

![]() An aerial view of mine dumps near Johannesburg. Photograph: Richard Du Toit/Minden Pictures/Corbis

An aerial view of mine dumps near Johannesburg. Photograph: Richard Du Toit/Minden Pictures/Corbis

The uranium leaches from the tailings and enters as run-off into surrounding streams and wetlands. A similar process occurs in abandoned mines underground, with polluted water seeping through porous rock as the mines flood. A tough white wasteland has hard boiled the soil where flowers and grasses used to grow. The soil has a pH of 2.67 – more acidic than vinegar. Potentially, the physical infrastructure of Johannesburg could be becoming radioactive as well. I think of my sister’s birth lottery, a marriage of cells and chemicals. Cancer of the blood. In that wasteland, I felt the quantum connectedness of all phenomena.

![]() New affordable housing constructed in front of large mine dump. (2013) Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg Photo: Jason Larkin

New affordable housing constructed in front of large mine dump. (2013) Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg Photo: Jason Larkin

It must be said that South Africans need to confront an uncomfortable history; what Gloria Wekker refers to as the paradoxes of race and colonialism in White Innocence, the passionate denial of racial discrimination and colonial violence.(3) A form of collective white amnesia seems to sugar coat the present neocolonial stalemate.

![]() Anti-Apartheid Resistance slogan from Author’s archive (1996)

Anti-Apartheid Resistance slogan from Author’s archive (1996)

![]() Gunshots at the gate: ‘Billy M’ led opposition by community members at Fuleni that culminated in a protest in April 2016. Photo: Phila Ndimande

Gunshots at the gate: ‘Billy M’ led opposition by community members at Fuleni that culminated in a protest in April 2016. Photo: Phila Ndimande

The idea of being and becoming in South Africa is about 'those who exit from the margins of society and feel excluded not only from the national wealth, but the very idea of belonging’.(4)

We should be able to open the Oxford dictionary and find that the 'noun' Coal is no longer defined as fuel, but rather as an adjective / heterogeneous / matter / ancestor / butch-trans-materiality(1) / remediator in which there are a variety of ongoing, mutable fizzes and connections between multiple species, and series of entanglements of coming into being, a metabolic mutualism not yet appreciated by a late capitalist society.

What forms of embodied knowledge does (Butch) Coal hold?

SPACE

Johannesburg. Jozi. Jo’burg. Joeys. More recently known as Gauteng. Some call it Mshishi, or Kwandonga Ziyaduma (where the walls rumble). The elders call it Shishisburg. Once it was called Egoli. The city quite literally built on top of gold, diamonds, steel, and coal. It sits on one of the largest deposits of precious metal in the world. Arguably one of the biggest cities not built on a major river or port - nothing to see here except highways and mine dumps and dust and passes which curve ever outwards towards the Congo basin.

The flyover city. The African continents ‘big apple’. Also known as the frontier town. A part of the wild west for the roughnecks and the lawless. More brothels than beer halls. A dense, post-apocalyptic air, with a heady mix of blade runner meets London or Bogota, the city known for its grime, crime and protest. There is a whiff of anarchy mixed with resistance, much of the streets crawl with gangsters and tstosis, everyone you knew had personal knowledge of someone who died violently. Yet there remains an indisputable energy and buzz in the cosmopolitan city, attracting thousands of newcomers to the city every day.

The lure of making it big in the city goes back hundreds of years. Johannesburg, with Dar Es Salaam, Nairobi and Addis Ababa are some of the cities with the longest history of human habitation. Longer than Athens, Rome, or Cairo.

Gold was discovered in Johannesburg in 1886, leading to a rush that attracted gold diggers, labourers, shopkeepers, and others from all over what was soon to become known as South Africa. The areas around the mines urbanized rapidly. Within 10 years of the mineral’s discovery Joburg had become South Africa’s largest metropolitan city. This dusty mining town has some of the highest quality anthracite in the world. South African Anthracite is a hard, jet black form of coal prized by the metals industry because of its high carbon and low ash content.

A Mine Dump near Viscount Road, Main Reef Road, Randfontein Johannesburg (2013). Photo: Jason Larkin

A Mine Dump near Viscount Road, Main Reef Road, Randfontein Johannesburg (2013). Photo: Jason LarkinIn the 1800s a new shipment of Europeans cut links with Holland and the Dutch East India Trading Route, breaking inland and calling themselves Afrikaners, after the continent. Originally farmers in the Cape Colony, they migrated to Johannesburg and Pretoria to became miners and traders. They formed a republic, called Die Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek, but were defeated by the British in 1902. South Africa as a political body, is a new one, created by the British and named The Act of Union of 1909. The Afrikaaners main political body party won the white election in 1948 and changed the existing colonial practice of separation of racial groups into a rigid ideology called apartheid*.

*The word apartheid literally means “apartness” or separate in Afrikaans, and more recently has been used in the Israel and Palestinian context.

While apartheid in South Africa was formalized in law in the late 1940s, the seeds for its creation were established years beforehand. The mining industry impelled the creation of laws and practices in South Africa which progressively disenfranchised the country’s indigenous peoples. Laws such as The Mines and Works Act (1911) effectively excluded blacks from skilled labour in the mines by stipulating that certificates of competency for skilled trades in the mines could only be issued to whites. These “colour bar” laws were engineered to prevent black workers from competing with white workers for the higher-paid jobs. This combination of punitive taxes and other laws and measures artificially induced black unemployment and restricted blacks’ job mobility, creating a supply of readily available cheap labour for the mines. This was effectively developed into an industrial system of exploitation and ideology of apartheid. Forced segregation and the destruction of communities followed. The mostly black and bohemian quarter, SophiaTown, was replaced with an all-white suburb called Triomf.

By 1958, Hendrik Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid became Prime Minister and Nelson Mandela was being tried for treason in the old Johannesburg Drill Hall. The revenues from gold and coal sustained the pariah apartheid regime after 1961 in the face of economic sanctions and military spending. For decades, anti-apartheid resistance grew, the eventual liberation of the people came in 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from serving a twenty-seven-year sentence on Robben Island in Cape Town.

It was the same year my father took me to the mines in Witbank for the first time; to witness large grey mounds of broken ground, bare tree stumps and trailing's of slurry and liquid which stuck to my shoes and fingers, staining them a dark black colour. The materiality of the fleshy dark substance appeared mutable, contingent, in a constant state of being and becoming. Beneath my feet was the geo-trauma of a mineralogical extraction site. I pick out the colours along the bank: red for iron, white for sulphur, green for copper, yellow for uranium. In my nostrils, the stench of burnt matches, skunk, and rotten eggs. Energy becoming material in this dark alterity.

This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralized acid mine drainage. Even after neutralization, this ever-growing, sludge-and-water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copper and cobolt. (2013) Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein Photo: Jason Larkin

This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralized acid mine drainage. Even after neutralization, this ever-growing, sludge-and-water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copper and cobolt. (2013) Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein Photo: Jason LarkinThe toxic result of over 150 years of irresponsible mining, there are currently estimated to be around 700 abandoned mine dumps with 600,000 metric tonnes of radioactive uranium buried in waste rock in and around Johannesburg. Making it undoubtedly the most uranium-contaminated city in the world according to Antony Turton, from the University of Free State’s Centre for Environmental Management.

The uranium leaches from the tailings and enters as run-off into surrounding streams and wetlands. A similar process occurs in abandoned mines underground, with polluted water seeping through porous rock as the mines flood. A tough white wasteland has hard boiled the soil where flowers and grasses used to grow. The soil has a pH of 2.67 – more acidic than vinegar. Potentially, the physical infrastructure of Johannesburg could be becoming radioactive as well. I think of my sister’s birth lottery, a marriage of cells and chemicals. Cancer of the blood. In that wasteland, I felt the quantum connectedness of all phenomena.

New affordable housing constructed in front of large mine dump. (2013) Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg Photo: Jason Larkin

New affordable housing constructed in front of large mine dump. (2013) Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg Photo: Jason Larkin

It must be said that South Africans need to confront an uncomfortable history; what Gloria Wekker refers to as the paradoxes of race and colonialism in White Innocence, the passionate denial of racial discrimination and colonial violence.(3) A form of collective white amnesia seems to sugar coat the present neocolonial stalemate.

Gunshots at the gate: ‘Billy M’ led opposition by community members at Fuleni that culminated in a protest in April 2016. Photo: Phila Ndimande

Gunshots at the gate: ‘Billy M’ led opposition by community members at Fuleni that culminated in a protest in April 2016. Photo: Phila NdimandeThe idea of being and becoming in South Africa is about 'those who exit from the margins of society and feel excluded not only from the national wealth, but the very idea of belonging’.(4)

Whose South Africa is this?

TIME

Requiem for a Nun, 1951 -William Faulkner

“If I am getting ready to speak at length about ghosts, inheritance, and generations, generations of ghosts, which is to say about certain others who are not present, not presently living, either to us, in us, or outside us, it is in the name of justice.... It is necessary to speak of the ghost, indeed to the ghost and with it”. -Derrida (1994 xix)

“I -is the total black, being spoken

From the earth’s inside.

There are many kinds of open

How a diamond comes into a knot of flame

How sound comes into a word,

coloured By who pays what for speaking”

-An excerpt from the poem Coal, by Audre Lourde

We all inherit coal.

We use it for energy, as a chemical source for synthetic compounds and extract metals to form alloys. Ethics, according to Karen Barad is about mattering. How do we come to matter in relation to other matter? I take a record of the intimate imaginaries of which I am entangled.

In all our struggles against colonialism and Apartheid we have struggled for these, and have insisted that no authority is greater than the will of the people. We have consistently told all the past rulers, that there can be nothing about us, without us.--The Peoples Mining Charter, South Africa 26th June 2016

On reading Plastic Matter by Heather Davis, I begin to dissect how coal has structured my life; which opens broader questions of inheritance. The literal consolidation of coal and the pervasiveness of whiteness and structures of supremacy. Certain bodies afforded privilege and conditions of possibility while other bodies are used as accumulator of toxicity and labour to extract coal.

What does it mean to have inherited this type of world? How do we deal with this intergenerational transfer of this inheritance?

Justice and temporality must be thought through together. As Leanne Naidoo explains: “South Africa is plagued by a generational fault line that scrambles historicity.”

What time is it?

Whose future, whose time? Yet to tell the time is a complex matter in this society.

‘We are, to some degree,post-apartheid, but in many ways not at all. We are living in a democracy that is at the same time violently, pathologically unequal. Naidoo argues that the student movements in South Africa areallowing one to 'hallucinate a new time, to kill the fallacies of the present: to disavow, no to annihilate, the fantasy of the rainbow, the non-racial, the Commission (from theTruth and Reconciliation, to Marikana, and...), even of liberation. The second task is to arrest the present. To stop it. To not allow it to continue to get away with itself for one more single moment. And when the status quo of the present isshut downthethird task –and these have been the moments of greatest genius in student movement –is to open the door into another time.'

Naidoo’s concept of stopping the present, shutting down the status quo and opening doors to another time confronts questions around petrified time in South Africa. What might be done with the material inheritances we would rather not possess? Where do we put our haunted carbon imaginaries?

The bulk carrier Queen Kobe is 189m in length and 32m in breadth, with a dead weight of 55444 tons. Its home port is Panama, its owner is from Japan, Tokyo and its manager is in Pusan, South Korea.In this photo, Queen Kobe is docked at Richards Bay terminal in South Africa.

The bulk carrier Queen Kobe is 189m in length and 32m in breadth, with a dead weight of 55444 tons. Its home port is Panama, its owner is from Japan, Tokyo and its manager is in Pusan, South Korea.In this photo, Queen Kobe is docked at Richards Bay terminal in South Africa.

What time is it?

Time flows from things.

Coal emits time.

I am the wall at the lip of the water

I am the rock that refused to be battered

I am the dyke in the matter, the other

I am the wall with the womanly swagger

I am the dragon, the dangerous dagger

I am the bulldyke, the dull dagger

And I have been many a wicked grandmother

And I shall be many a wicked daughter

- From “She Who”, Judy Grahn

Lesbian. Lesbo. Lezzie. Licker. Carpet Muncher. Tomboy. Butch.Bull Dagger. Butch Dyke. Dyke on Bike. Queen of Bull Dikery. One of the boys. Walks that way. Talks that way. Butch is a visible way of being. Of refusal. Of non-conformity. A form of marginalized masculinity if you will. What Butch means depends on who you ask. Butches see Butches differently and in doing so, we can reframe the extractive, male gaze.

Judy Grahn speaks of ancient Ceremonial Butch as warriors who saw with cunt eyes and held institutional power. Through my reading of butch lesbian poets, I am offered a newfound sense of historical belonging, which for Queer people who were told we had no history, brings a profound sense of relief. In this present moment of climate justice and rising authoritarian power, Grahn invokes the goddess of erotic love, Inanna –who rules with cunt power and protects nature.

An awareness that “mineral substances are expendable and incapable of renewal; and organic plants and animals which are characterized by their ability to reproduce and multiply”.(5)

Butch-trans-materiality as co-evolving force in the cosmos, rather than a self-determining one.

Adrienne Rich defined the feminist project as way of being disloyal to one’s civilisation, out of love for that same civilisation. All Butches concerns are linked with the political; confrontations of territorialization, deterritorialization and reterritorialization. A butch possesses a sense of political being-in-world; an attentiveness; a desire for justice. Butch is a certain manner of motion. It is one way of becoming in the world as a kinetic phenomenon. That way, the way of Butch, is not in terms of aesthetic, but in terms of the degree of madness, of daring, of escape.

To be Butch is to have an unfinished relationship with the present. To break up with fossil fuels. To exist outside of time. Butch looks to redirect the extractive gaze toward another view of decolonial exploration; the interiority of matter and queer ancient ways of being and becoming. To be Butch is not to accept standard notions of family and state, or coal as a fossil fuel. Butch demands alternatives.

The meeting of the private with the historic and the geologic becomes an articulation of ecological resistance.

Butch is a vision of the world in terms of transitional– but a particular kind of transit. It is the love of the knotted, rhizomatic, fragmentary, the “entangled”, of things being-in-between; shifting between dynamic and receptive; sometimes in silence. Acutely aware of the continuum between natural, planetary, and cosmic.

This is a more than human event; the new wave of butch-trans-materiality(6); belonging in unbelonging; of understanding how things come to matter, in relation to other matter.

Becoming earth / animal / more than human – or becoming imperceptible are profound breaks with established patterns of thought and introduce a radically imminent planetary dimension. Defamiliarization is a sobering process of (Butch) discontinuity allowing for alternative frames of reference which are open-ended, inter-relational, multisexed and trans-species (Braidotti, 2012)

How do I think through my relationship to coal, which is pervasive, toxic, and polluting the air we breathe? There is an urgency to destabilize, to subvert, to invest in fluidity by challenging my ontological inheritance.

In me, is the urgent need to Queer the Coal. Yet this word Queer is so contested, so commodified, so hip, so in use, so academic. Mel Y Chen writes:

’Given ecology’s attention to networks of mutually transforming and sustaining elements in a system, ecological thought belies any simplistic separation, functional or otherwise, between an individual and its surroundings. Ecology thus communes easily with a notion like “queer,” particularly in the sense of queer’s investment in diffusive energies and the traffic underneath and beyond idealized and atomized scenes of sexual reproduction. […] Yet queer ecologies also encounter friction with that notion of “queerness" that has, for better and worse, continued an investment in human-exclusive politics of dyadic, embodied, gendered engagement couched in identity. Similar tensions appear around the term “community,” a concept that has often been used to reify a monolithic understanding of certain queer humans— those who happen to live (well enough, it’s assumed, and whitely) in u.s. imperial capitalism…'

In the introduction to her 1993 essay collection Tendencies, Eve Sedgwick famously defined queer as 'the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of one’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically.'

Through the act of queering, I want to reconfigure Butch Coal as post-human, an open mesh of possibility.

There is an unremitting emphasis in my acts of Queering the Coal to unearth the fluid, über-inclusive, mutualistic, unknowing, preposterous, impossible, absurd and that which is ultimately unrepresentable. Through acts of Queering I want to make sense and make space for this inherited material.

A metabolic love story between crushed coal and pink oyster mushroom

As a material witness to the injustices of coal mining in Johannesburg, I start to ask questions about biological inheritance at the Institute for Environmental Biotechnology at Rhodes University in South Africa. According to Stuart Cowan, the power global mining companies who own the mines also own the mineral rights, with little empathy for the communities and environmental impact of their ongoing extractive practices.

Cowan and I discuss the humanitarian crisis in South Africa which has become a sacrifice zone for Petro-imperialism. I ask him about the research papers he has published in which he describes a process called FungCoal, which exploits fungi-plant mutualism to achieve biodegradation of weathered coal, which in turn, promotes reinvigoration of soil components, grass growth and re-vegetation. This process is a Fungal colonisation and enzyme-mediated metabolism of waste coal by Neosartorya fischeri strain ECCN 84. According to his experiments, the results show that waste coal supported fungal growth.

What is this metabolic mutualism between coal and fungi?

Could these Queer metabolic encounters forge a new science of the world “sociogeny?”(8) (Fanon) from the riff zones to create adaptative truths and justice?

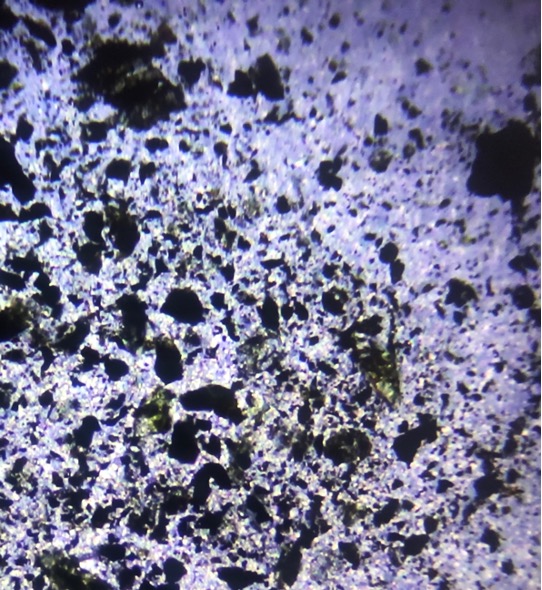

I am in my studio with a microscope examining the materiality of coal. It looks dark and shiny and fragile and beautiful. I place a drop of my saliva into the microscope and watch it sashay and seduce the coal. We are all melting. I feel a performative 'coming down to earth'(9) – in the form of powerful grief emerging in relation to the Butch Coal beneath the microscope. I think of ammo globulin transfers and bone marrow transplants and Hickman lines. I think of contaminated water and air and lungs. Of illness as metaphor. Of a dyke for president. A feminist constitution. Butch Materialism. The Moon is waxing. Aufschmelzen.

Through the (re)queering and (re)creation and (re)invention of minerals can we regenerate the Capitalist Extractive Zone?

This marks a shift in my thinking from intergenerational time to Queer time. From a patriarchal inheritance to a biological inheritance. Deep time. Ancestral time. Coal post-fuel as the connective seam through places and time.

How can looking and working beyond linear progressive and globally synchronized time contribute to a more plurally-determined and sustainable existence?

MATTER

- Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning

“Central to my analysis is the agential realist understanding of matter as a dynamic and shifting entanglement of relations, rather than as a property of things.”

― Ibid.

We revolt, simply because …. We can no longer breathe.

- Franz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution

It is the month of May 2022, and I am in the English county of Devon. Outside I can hear the foxes letting out the vixen call. It is mating season. The night is thick with desire. The screen connects. The connection is clear. I find the courage to speak. “What does it mean to follow a ghost?” This is the first question I ask Karen Barad who blinks back at me, smiling. They open their mouth and words emerge in a low, confident tone.

“Justice and temporality must be thought through together. Ghosts are not traces of the past if we think of the past as done. Ghosts are supposed to wake us up to the fact that the past is not over. There is something present-not-present about a ghost, right?” Professor Barad is wearing a black t-shirt and thin rimmed black glasses.

![]() Image: Professor Karen Barad and myself in video conversation about Queer Minerals and Butch Coal (4th May, 2022)

Image: Professor Karen Barad and myself in video conversation about Queer Minerals and Butch Coal (4th May, 2022)

Inside my chest, my heart beats and bursts up towards my throat. Ghosts are supposed to wake us up to the fact that the past is not over. I am haunted by ghosts, reminding me that the present is not over. The present is uninformed, misguided and mad. Time has never felt more disjointed, out of sync.

My research has led me to Barad, who has given me the framework, through Agential Realism to reconfigure coal as a different imaginary. To experience past, present, and future as enfolded. I blink into the screen and imagine myself as an electron. Barad in Santa Cruz and me, across the globe in Devon, England. There is no inheritance without a call to responsibility. Disjointed time and space, entanglements of here and there, now, and then, a ghostly sense of discontinuity.

![]() Microscopic Coal, Saliva (2022)

Microscopic Coal, Saliva (2022)

I explain to Barad that I believe I may have taken a quantum leap. Well, I hope that they would agree and define my research as a quantum leap. My understanding of change, up until now has been caught up in the idea of continuity. My patriarchal inheritance / blindspot rooted in determinism. A Faustian bargain into which I entered upon my father’s death. My labor is assumed to be a given commodity with which to continue the coal trading practice. Through the rejection of a familial material inheritance, I would rather not possess, I have taken a Quantum Leap, which according to Barad, who now nods and confirms, “is a leap outside of time.”

A leap outside of time. I simply love this idea. Queer Quantum Time. To be Queer is to exist on the fringes, in the corners, outside, never inside. To choose not to be seduced by linear notions of family, nationhood, and history.

Another important reference is sociologist Avery Gordon’s concept of “haunting”. For her, to be haunted is not the same as being exploited, traumatized, or oppressed, although it usually involves these experiences or is produced by them. Her use of the term describes an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence makes itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely. Haunting situations happen when home becomes unfamiliar; when the experience of being in linear time is suspended; when your bearings in the world lose direction.

- Franz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution

It is the month of May 2022, and I am in the English county of Devon. Outside I can hear the foxes letting out the vixen call. It is mating season. The night is thick with desire. The screen connects. The connection is clear. I find the courage to speak. “What does it mean to follow a ghost?” This is the first question I ask Karen Barad who blinks back at me, smiling. They open their mouth and words emerge in a low, confident tone.

“Justice and temporality must be thought through together. Ghosts are not traces of the past if we think of the past as done. Ghosts are supposed to wake us up to the fact that the past is not over. There is something present-not-present about a ghost, right?” Professor Barad is wearing a black t-shirt and thin rimmed black glasses.

Inside my chest, my heart beats and bursts up towards my throat. Ghosts are supposed to wake us up to the fact that the past is not over. I am haunted by ghosts, reminding me that the present is not over. The present is uninformed, misguided and mad. Time has never felt more disjointed, out of sync.

My research has led me to Barad, who has given me the framework, through Agential Realism to reconfigure coal as a different imaginary. To experience past, present, and future as enfolded. I blink into the screen and imagine myself as an electron. Barad in Santa Cruz and me, across the globe in Devon, England. There is no inheritance without a call to responsibility. Disjointed time and space, entanglements of here and there, now, and then, a ghostly sense of discontinuity.

I explain to Barad that I believe I may have taken a quantum leap. Well, I hope that they would agree and define my research as a quantum leap. My understanding of change, up until now has been caught up in the idea of continuity. My patriarchal inheritance / blindspot rooted in determinism. A Faustian bargain into which I entered upon my father’s death. My labor is assumed to be a given commodity with which to continue the coal trading practice. Through the rejection of a familial material inheritance, I would rather not possess, I have taken a Quantum Leap, which according to Barad, who now nods and confirms, “is a leap outside of time.”

A leap outside of time. I simply love this idea. Queer Quantum Time. To be Queer is to exist on the fringes, in the corners, outside, never inside. To choose not to be seduced by linear notions of family, nationhood, and history.

Another important reference is sociologist Avery Gordon’s concept of “haunting”. For her, to be haunted is not the same as being exploited, traumatized, or oppressed, although it usually involves these experiences or is produced by them. Her use of the term describes an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence makes itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely. Haunting situations happen when home becomes unfamiliar; when the experience of being in linear time is suspended; when your bearings in the world lose direction.

Barad tells me we are kin.

I pick up a pair of quantum scissors to de-/re-territorialize — that is, reconfigure — the landscape.

To cut it down.

I reassemble it in queer forms.

By attaching myself to the matter, I explode the boundaries of humanism at skin level and turn the undutiful daughter into a generous proliferation of hallucinatory, planetary, and queer relations to coal post-fuel.

Butch coal is a queer awareness of mutually transforming elements, an invention of a chemical vocabulary and language to imagine all the sustaining possibilities we face.

The undutiful daughter takes the side of the un-tagged, undocumented, unmarked, and (as-yet) incomputable, while studying in depth the father’s systemic blind spot. (Mende, 2018)

Mende speaks of the archive’s metabolic condition as transforming and creating space for new ideas, both molecular and mineralogical. Being Butch is speaking with ghosts - an epistemological unmooring, peering into and dealing with the muck and violence of the extractive zone to construct decolonial alternatives. This is what counts: the undutiful daughter always dreams of a location that is deterritorialized in the world, searching and finding a language that allows one to think towards “a future different from the present”. (Ibid) What material lines of flight exist which will continue to drive mineralogical revolution? And how will this impact climate justice?

As Deleuze and Guattari observed the plateau cannot hold.

We don’t only inherit the past, we inherit the future too.

Notes

1. In our conversations, Karen Barad asked me if this imploded term, butch-trans-materiality exists? To the best of my knowledge it does not, until now. TransMaterialities is a term that arose in the planning of UCSC’s 2009 “TransMaterialities: Relating across Difference” Science Studies Cluster graduate student conference, co-organized by Harlan Weaver and Martha Kenney, with faculty sponsors Donna Haraway and Karen Barad.

2. The concept of an undutiful daughter is elaborated further by Doreen Mende in her article on Eflux: The Undutiful Daughter’s Concept of Archival Metabolism. Mende quotes Braidotti “There is something monstrous, hybrid, and vibrant in the air; dear readers, I feel new ideas coming our way. We just do not know yet what this corpus can do.“ The undutiful daughter learns a language she does (not) want to learn but must. The undutiful daughter who refuses the paternal law but who also believes in the archive’s futuristic power. She cannot (not) participate in the language “of what can be said,” but she does so in accordance with her own learning processes, vocabularies, and pathways. She is already two: a daughter and an undutiful.

3. Gloria Wekker quotes Edward Said in her introduction; “All the energies poured into critical theory, into novel and demystifying theoretical praxes – have avoided the major, I would say the determining political horizon of modern Western culture, namely Imperialism.

4. For more see: The Contested Idea of South Africa which tackles the question: Why is the idea of South Africa so contested? Today the new struggles ‘for South Africa’ and ‘to become South African’ are inextricably intertwined with complex challenges of transformation, xenophobia, claims of reverse racism, social justice, economic justice, service delivery, and the resurgent decolonization struggles reverberating inside the universities. This book covers the genealogy of the idea of South Africa, exploring how the country has been conceived of by a broad group of actors, including the British, Afrikaners, diverse African nationalist traditions, and new formations such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), Black First Land First (BLF), and student formations (Rhodes Must Fall & Fees Must Fall)

5. An interesting read on raw materials and the industries based upon them, for further reading see Industrial Archaeology, Chapter six, page 86.

6. Please see Karen Barad’s brilliant essay onTransMaterialitiesTrans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings and the use of Harlan Weaver’s term.

7. Borradori, Giovanna. Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003, Part 2.

8. That a phenomenon is sociogenetic thus indicates that it is socially produced, as opposed to ontologically given, immutable, or static.

9. The attraction of Trump is that he has managed to harness this context to his own benefit: “Trumpian politics is not ‘post-truth’ but post politics, a politics with no object, since it rejects the world that it claims to inhabit” To resist this, Latour proposes that we need to come down to earth; to land somewhere. He names the new place we need to inhabit “the Terrestrial”. Rather than being the framework for action, the Terrestrial participates in the action. Humans are no longer the only actors, as the earth now comes fully into play. But what is an appropriate political approach in the face of this?

FURTHER READING

Barad, Karen, (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway, Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Duke University Press

Baraitser Lisa, (2017), Enduring Time, Chapter 4 Delaying, Bloomsbury Academic

Becker, Derick (2020) Neoliberalism and the State of Belonging in South Africa, Palgrave Macmillan Cham

Braidotti, Rosi Bignall, Simone (2019), Posthuman Ecologies, Rowman and Littlefield Ltd

Chen, Mel Y (2012) Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, Queer Affect. Duke University Press

Fanon, F. (1952) 1986. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto.

Giffney, Noreen, Hird, Myra (2008) Queering the non-human, Routledge, London

Holland, Heidi (2002) From Joburg to Jozi, Stories about Africa’s infamous city, Penguin Books

Haraway, Donna J (2016), Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press

Johnston, Jill Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution (New York: Touchstone, 1973).

Lorde, Audre “Learning from the 60s,” in Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches (Crossing Press, 2007), 138.

Mbembe, A. 2008. “Aesthetics of Superfluity.” In Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis, edited by S. Nuttall and A. Mbembe, 37–67. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.10.1215/9780822381211

Mortimer-Sandilands, C. and Erikson, B (2010) Melancholy Natures, Queer Ecologies Indiana University Press.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J, Ngcaweni Busani (2021) The Contested Idea of South Africa, Routledge

Tsing, Anna, Barad Karen (2017), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, No Small Matter, Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of SpaceTimeMattering, University of Minnesota Press.

Weaver, Harlan (2016) “Monster Trans: Diffracting Affect, Reading Rage.” solicited for reprint in Transgothic. NewYork, NY: Routledge, tba.

ONLINE

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/93/215339/the-undutiful-daughter-s-concept-of-archival-metabolism/

https://www.apartheidmuseum.org/

https://www.constitutionhill.org.za/

https://www.magicmushroommap.com/

https://macua.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Peoples-Mining-Charter.pdf

https://www.elasticfiction.co/

https://www.barneypau.com/

https://pascaldreier.com/

END NOTES

I am grateful to Ros Gray and Jol Thoms and Ian Hunt for their unwavering patience and enthusiasm. I would like to thank Karen Barad for graciously accepting my proposal to have some of our conversation diffractively dispersed throughout the essay. Barad’s materiality of political imaginaries, justice-to-come and the endless possibilities for making queer alliance with nature's nonessentialist nature are influential in my research.

Thank you to Rich Daniels from the Hopewell Colliery and museum in Bristol who generously provided me with large chunks of coal for research.

A note of appreciation to Stuart Cowen who spent hours on the phone to me explaining the science of bio-remediation through fungal degradation around mine dumps.

Thanks to Laure Vigna whose bacterial revolution and research was influential in my own mineralogical exploration as well as Fatima Alaiwat for the ongoing anarchist conversations around belonging through food.

As ever, I am grateful to Leila El-Kayem for her feedback, editing skills and support.