Djuna O’Neill

While living

a life of dis/connection through zoom tutorials, chatrooms, multiplayer games

with simple objectives and rectangular chat-boxes or single player games in

expansive fantasy worlds, I trudge through wet, misty bog; cheeks stinging and

feet cold in rubber boots. In both spaces I wander, get lost, lose orientation

and find my bearings through landmarks I grow familiar with.

With my mind still reeling in pastel

pink worlds of uniformly falling raindrops and alien flower petals suspended in

a static breeze, I visualise the expanse of sprawling trenches and purple

heather from a drone’s-eye view. I am a character, collecting items I dig from

the mud as I wander in a first-player game and add the objects, removed from

their temporal stasis, to my inventory: tuft of bog cotton, stick for throwing

in the pools of dark water which collect in the pits of cut bog, a scrap of

metal (age unknown), shard of bone (a recently deceased animal or a relic

preserved and discarded by the bog?). Gnarled roots rise from the murky black

pools around me, though no trees grow on this flat plane. Are they the roots of

ancient forests, uncovered from their peaty sanctuary by the years of turf

cutting which scrape away the strata of decades?

Bog Bodies

Bog bodies, some say, were sacrificed here in the belief that the watery depths veiled portals to otherworlds. (1) In “composing” our futures, as Latour proposes, a dismantling of ideologies must occur. Fredengren delves into the material realities of halted decomposition in bogs and crannógs (2) as a way to peer around the conceived linearity of time and speculate at how these apparitions of temporal anomaly might have dissolved previous beholders ideas of the steadfast continuity of their surroundings. These may have manifested as sacred hierophanies (3), apparitions which bestowed the landscape with a reverent importance. Perhaps bygone discoverers of peat-preserved relics accredited these appearances from alien timescapes to a passage between worlds.

The damp presses

against my papery eyelids. Dark water seeps between my fingers and I feel the

wetness of the earth under my fingernails. An acrid dampness cloys in my

nostrils.

As I step out across the unending

flatness, the unctuous ground shifts and heaves beneath my feet. A hazy sky

shimmers above. Below, the detritus of millenia swells in a sopping sediment. A

palimpsest, therein lie the remains of centuries of culture, steeping in a

state of permanent decay. Subterranean memory. Porous limits and entangled

stories.

Old Croghan Man’s fingerprints are of

a pattern still widespread in Ireland.(4)

Bogs have

always existed on the farthest reaches of lived landscapes; their liminality

the provider of refuge for many an escaped or outlawed person.(5) Tories (dispossessed Irish persons turned outlaws) and thieves found shelter

and refuge in the bogs, their protean (6) nature providing an

advantage to the resistant natives.(7) Protected by its uselessness, its

viscosity resists the spread of neoliberal market-driven land value. Derek Gladwin frames the bog as a redemptive site of

alterityin its economic marginalisation,

against a context of the change in land values to its becoming hungrily sought

after. (8)

Perhaps

hauntings are not the presence of other times but of otherworlds. In a culture

where otherworlds have always existed alongside our own, this is undoubtedly an

easier feat of interpretation. Samhain, halloween night, is in Irish tradition

the night when the veil between worlds is at its thinnest. These spirits and

ghouls come not from stuck pasts but from parallel presents. Infact,

considering the theories that bog bodies have been sacrificed to the

underworlds of earthly goddesses through the boggy depths; the murky, peaty

pools acting as liminal portals, we could say that bog bodies are heralds of

another world.

The emotional fatigue of the unreachable intimacy of

techno-interfaces drags against the enticing boundlessness of undiscovered - uncreated - worlds. Weary from glossy 72

ppi faces and lagging conversation we dig our hands into the soil in search of

the boundaries of our own body. The

screen shows us limitless new worlds, dozens of fictional environments, but in

reaching they encounter only cold glass. How can we feel the static breeze on

our skin? Glossy thresholds between worlds, watery

and earthly or static and phosphorescent. A liquid interface; the bog body

emerges from his oozing resting place and strides into a shimmering expanse of

low poly vegetation, below a hazy sky and flat disk sun.

Digitising as a commonning practice

Beansí

The beansí,

beansídhe, banshee, wanders the paths between worlds. From where she walks, the

sounds that escape her parted lips - guttural, ethereal, shrill and rumbling

all at once - slip through the veils that hide one world from another. Temporal

or spatial, the soundwaves of her lament bear resonances of loss and hope

across borders.

Latour describes the method needed

for considering the future of our actions as an act of composition.(1) To plunge into controversy, to leave behind separations between what is

progress and what is archaic, to take interest in the key issues of living

conditions and to make those a priority in terms of production. These are the

methods he claims must be used in leaving behind the slogan of modernity and

environmentalising the future.

Silvia Federici, amongst others, in

searching for the roots of modern capitalism, emphasises the significance of

the process of Enclosure in rural medieval england. Through the loss of the

commons, space for peasant solidarity and sociality was destroyed - spaces of

social communion, and a source of food production for unwaged citizens.

Notably, Federici describes the emergence of an archetypal character - widows

robbed of the means of subsistence resorted to begging and theft to survive. This

occurs alongside the rising demonisation of the witch throughout Europe.

Thinking about the role of stories

and mythmaking in the collectivising

of social movements, (2) is it not probable that stories, whose ability

to transgress time is proven in the richness of folklore (3) heard to

this day, retain the tunes of the collectivising rallies of radical subaltern

land theft protestors? In considering the loss of commons as spaces for

communal belonging, let us consider folklore - to include practices containing

storytelling, craft, medicinal and land related knowledge - as a form of

commons, which persisted when relations to land were severed.

Dublin

based vocalist group Landless sing of the threads of resistance that are

carried through song and folklore. Through the ghostly sounds of their tracks Caoin i and Caoin ii, theyevoke

histories of quotidian life suffused with spectral apparitions, supernatural

occurrences, and the haunting potentials of liminal other spaces. The track

title, Caoin, translates to a cry or

a lament, which when heard alongside the band’s name brings to mind not only

references to folk figures such as the banshee, with her ethereal and ghostly

cry foretelling death, but also references to complex histories of land

dispossession in Ireland.

Monuments

of ghostly bygone ages, scanned and uploaded to networks of intangible

materials, unreal objects and hollow worlds. Does a stone still speak the same

words in its virtual tongue?

Open source creative programs and the networks of material and knowledge sharing which grow around them incite the sense of experiencing a community rooted through cybernetic threads. I visualise the paths of shared files and experience as faintly luminescent spider webs, emitting from a morphing network of communal information. Can digital spaces hold the solidarity of a commons? Through virtual technologies of storytelling we continue to share what we know.

Cailleach

Simultaneously

creator and destroyer, generous and inimical, the hag belongs to, forms, and

embodies the landscape itself. Mountains grow from the rocks that tumble from

her gathered apron as she strides over the land.

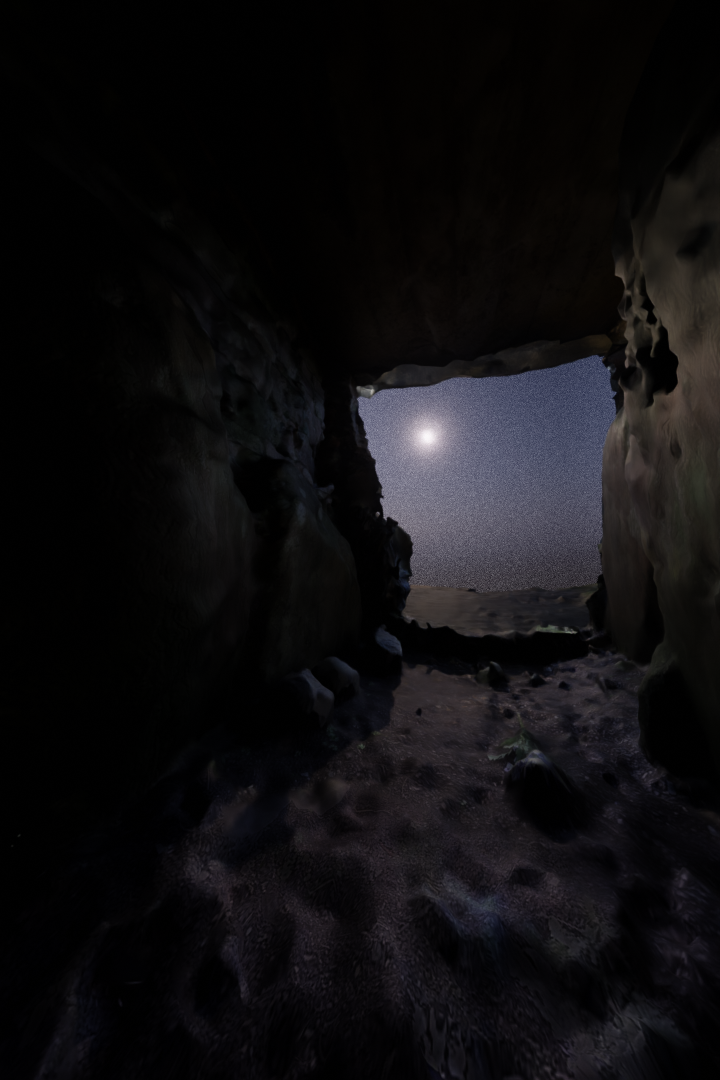

Vast scapes of faded technicolour, boulders

of pixelated limestone house digital remains of future realities. The Cailleach

creates her reality, sculpts and texturizes. Canopies of rock house digital

relics. Wander deep into the cavernous womb of Cairn T, the narrow dark passage

lit by the dim blue glow of the ambient light and discover within the archaic

drawings. They depict pasts, a multitude of presents and possible futures. In

the synthetic light they appear to move, slowly. Spirals twist into themselves

and floral shapes appear to grow tendrils, reaching, sensing, ready to wrap

tightly over their find.

Below the shimmering apparitions of

illustrious carvings lies a wide and shallow basin. Water rises in the basin,

beginning as a cloying layer of condensation, droplets roll down and gather in

its pit, forming a small puddle. The petroleum-tinted surface of the water

rises, slowly, encompassing the items that lie there: a chipped and yellowed

bone fragment, a comb, its teeth broken or missing, a ring. The water laps,

slowly, moved by an unfelt wind.

I stride out into the realm of my

creation - pink grass folds under my feet. The apron I wear is gathered into a

sack, and full of clay: material, unformed and ready to become the stuff of the

lived world. It crumbles and falls to the ground beneath, becoming mountains,

boulders. In the seconds it takes to fall, dolmens and cairns form. Piles of

stones sit precariously atop one another. It is my eternal journey. As I

stride, generations lapse between my toes. Civilisations rise and fall as the

weight of my footsteps creates lakes, moulds the earth into ridges and valleys.

The weight of the clay I carry causes me to exert myself and the sweat runs

down and becomes rivers. I rest and trees sprout from my feet. In the time that

it takes me to catch my breath, the trees have grown and died. They decompose

and mosses grow, a flat expanse of thousands of years of vegetation, decayed

into a world of black earth.

By the end of my journey I have

tired. I rest, and the plants stop growing. In my negligence, the sun forgets

to warm the earth and it grows cold and frozen over. A barren world emerges.

Where once I marvelled at the wonder of the world I had created, I now grow sad

to see it. I grow cold, and with me the world frosts over. A bright expanse of

rippling ice. Its surface shines like the opaque glass of an idle screen.

In The

Lament of the Old Woman of Beara, the cailleach is old and reflects on the ebbs

of the life she’s lived. In a state of solitary wintery reflection, her morose

tone reflects the harshness of the wintery conditions she is accredited with

delivering. Some stories say that in the

spring she transforms into her younger self and her cyclical journey begins

again. A stone sitting atop the Beara Peninsula and overlooking the bay is said

to be her petrified form.

Places

across Ireland and Scotland bear her name, and the roles she personifies in

stories are manifold. Sometimes a wicked trickster hag; others a young goddess

of the land. Her reknown has existed too long to extricate the threads of her

person from the stages of cultural and religious influence.

In what Bruno Latour has called the “second scientific

revolution”, the agency of living beings is recognised as a major considerable

factor in the movement of powerful forces which dictate our conditions of life.

In Irish mythology, the prevalence of otherworlds is

analogous to a perceived volatility of the surrounding environment. Stories

such as the Seachran Sí describe

mountains that shift and grow before an unsuspecting traveller, rivers flowing

on dry land and paths entwined into never ending loops.

“When explaining the strange and sudden forms of supernatural

disorientation experienced by individuals travelling through the rural

landscape, reference is consistently made to spirits beyond the bounds of the

mundane realms of the human community. Herein are displayed sentiments by which

the wider landscape is ordered and arranged, in that it is not understood as

being inert and unchanging but dynamic and subject to potentially drastic and

sudden shifts. These narratives then, and the body of lore and folk belief that

they comprise, replete with dramatic abstractions and ornate aesthetic

qualities, offer insight into the mechanism by which the rural landscape has

been humanised, mapped out and maintained, not only according to physical

demarcations and boundaries, but to metaphysical ones.” (bluirini bealoidis)

Latour’s analysis of the second

scientific revolution as a recognition of the conditions of life in which

we find ourselves being the product of other life - living beings whose lives

overlap with ours, can be likened to the recognition of an unpredictable

changeability in the landscape inhabited in Irish folklore. On global and micro

levels, living beings exert forces on our lived atmosphere - a virus can, as we

have discovered, reduce supposedly infallible societal systems of movement and

production to a halt in a matter of weeks.

The Cailleach, embodying traits of both mother/fertile and hostile/harbinger of death, personifies the equally productive and destructive powers of nature.

Otherworlding as commoning practice through

technologies of storytelling:

Using Niemanis’ description of a posthuman

phenomenological interface of perception which includes “both a tongue and a

water quality autosampler, both a sensitive fingertip and a DNA

sequencer”, cultures of storytelling and

oral tradition can be included in an expanded sensory apparatus. To allow the

supernatural or the other, be that in

science fiction/speculative fabulation, traditions of storytelling or

contemporary artist film, might engage an attentiveness to the potentialities

of perspectives beyond those on which our regularly frequented worlds are

built, engaging a curiosity and care in the way we relate with the human and

beyond.

A “torquing of our imaginaries so that matter

can matter differently”, “fostering new ontological dispositions towards the

world and worlds at large”. (Niemanis, 2017), (Palmer and Hunter, 2018)

Noticing Attunes Us to Worlds Otherwise (Gan, Tsing, Swanson

and Bubandt 2017)

Footnotes

Bog Bodies

1.“Staying within the context of Irish folklore and

literature, there is good evidence to suggest that concepts of preservation and

decay are intimately associated with ‘being in’ and ‘leaving’ the otherworld…

More recently, Giles (2009) proposes that the deposition of bog bodies in

wetlands might have intentionally used bog pools as portals to the otherworld.

Interestingly, other elements of Irish literature describe waters as places

where hierophanies occur, and where the holy would emerge to become manifest in

the world of the living.”

2.A

crannóg is an archeological site, consisting of a partially or entirely

artificial island, usually found in lakes of Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

(Fredengren 2016)

3.

Hierophanies - sacred apparitions. (Fredengren, 2016)

4. Portfolio: Out of

the Bog Author(s): Frank Miller

5. Swamps

and wetlands provided shelter and refuge for escaped slaves. Dimitris

Papadopoulos in Experimental Practice(2018) outlines the role of wetlands as a refuge for insurgents.

6. Protean -

Tending to or able to change frequently and easily.

7. In

Ireland, dispossessed persons were relocated to the boggy landscapes of

Connaught. The boglands surrounding the Pale provided shelter to outlaws and

bandits who raided the English settlers, giving them an association of barbaric

wasteland. Tories was the name given

to Irish cattle raiders. A review of Derek Gladwin’s Contentious Terrains (2016)vby Eóin Flannery.

Beansí

1. In a

series of interviews with Arté, 2021.

2. In Letters of Blood and Fire: Primitive

Accumulation, Peasant Resistance, and the Making of Agency in Early

Nineteenth-Century Ireland, Dunne analyses a collection of threatening

letters left by land protesters to landlords, as part of a broader state of

agrarian social conflict. The peasants resisting primitive accumulation

sustained their sense of collective efficacy through mythmaking to create a

pan-regional collective identity.

3. The

commonly used words folklore and superstition seem ill fitted to the

subjects I want to discuss; superstition denotes an unfounded mistrust or

paranoia, while the word folklore seems to belittle the wealth of knowledge

tied into the word. Patricia Dominguez, in a text published by Gasworks,

dismisses the word as reductive and charged in politics of power; “Folklore is

the name of a colonial strategy. Folklore is a way for colonial elites to erase

indigenous worlds and neutralise ancestral histories. It’s a way to keep them contained,

to relegate them to the margins, to exoticise them. Folklore is a way to freeze

time, transforming open and unsolved historical processes into a souvenir for

tourists. And yet, ancestral history is still happening. It is simply going

down other roads, in unexpected ways.” (2019) Rather, I think the Irish word Béaloideas seems more apt to the

subjects I discuss, translating roughly to mouth/oral(béal) teaching/instruction (oidis),

I think the phrase allows for more space to encompass the traditions of orally

relayed storytelling but also of craft, medicine, ritual, and the more

ephemeral and intangible concepts of seeing, or ideological beliefs of the

conditions of the world.

Images

1. Colaiste

Íde Ogham Stones, image from gaelic.co/ogham/

https://i0.wp.com/gaelic.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Colaiste-Ide-Ogham-stones-Co-Kerry-purple-negative-1920x1280-compressed.jpg?fit=1920%2C1280&ssl=1

2. Bog,

Galway, IE.

3. Digital

scanning of Ogham stone, Lugnagappul, Co. Kerry, from Irish and Scottish researchers

to investigate ancient Ogham script, Maynooth University.

https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/news-events/irish-and-scottish-researchers-investigate-ancient-ogham-script

4, 5 &

6. Still render of 3D scene, depicting Cairn T passage tomb, Loughcrew, Slieve

Na Calliagh. 3D model created by Megalith Archive,

https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/loughcrew-aa0c7376f76040f7b124fc0197827f7d

Gifs

Background.

Animated 3D scene.

1. Animated

scene including 3D model of Neolithic Ground and Polished Axe created by The

Hunt Museum, Limerick. Stone axe head found in Rockbarton Bog, Lough Gur,

Limerick.

https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/neolithic-ground-and-polished-axe-47026b76c7d847ffb9659fd4d4d75cc3

2. Animated

3D scene including quote from Fredengren (2016).

3. Animated

sentence, reading “Does a stone still speak the same words in its virtual

tongue?”

4. Animated

3D scene depicting a scan of a rock on the shore of Lough Corrib.

5. Animated

3D scene depicting Cairn T passage tomb, Loughcrew, Slieve Na Calliagh. 3D

model created by Megalith Archive,

https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/loughcrew-aa0c7376f76040f7b124fc0197827f7d

6. Animcated

3D scene depicting a model of mountains in Connemara, downloaded from Google

Maps and Nasa Elevatino data using Blender GIS addon.

Bibliography